TL;DR: November’s Go Flux Yourself marks three years since ChatGPT’s launch by examining the “survival of the shameless” – Rutger Bregman’s diagnosis of Western elite failure. With responsible innovation falling out of fashion and moral ambition in short supply, it asks what purpose-driven technology actually looks like when being bad has become culturally acceptable.

Image created on Nano Banana

The future

“We’ve taught our best and brightest how to climb, but not what ladder is worth climbing. We’ve built a meritocracy of ambition without morality, of intelligence without integrity, and now we are reaping the consequences.”

The above quotation comes from Rutger Bregman, the Dutch historian and thinker who shot to prominence at the World Economic Forum in Davos in 2019. You may recall the viral clip. Standing before an audience of billionaires, he did something thrillingly bold: he told them to pay their taxes.

“It feels like I’m at a firefighters’ conference and no one’s allowed to speak about water,” he said almost seven years ago. “Taxes, taxes, taxes. The rest is bullshit in my opinion.”

Presumably, due to his truth-telling, he has not been invited back to the Swiss Alps for the WEF’s annual general meeting.

Bregman is this year’s BBC Reith Lecturer, and, again, he is holding a mirror up to society to reveal its ugly, venal self. His opening lecture, A Time of Monsters – a title borrowed from Antonio Gramsci’s 1929 prison notebooks – delivered at the end of November, builds on that Davos provocation with something more troubling: a diagnosis of elite failure across the Western world. This time, his target isn’t just tax avoidance. It’s what he calls the “survival of the shameless”: the systematic elevation of the unscrupulous over the capable, and the brazen over the virtuous.

Even Bregman isn’t immune to the censorship he critiques. The BBC reportedly removed a line from his lecture describing Donald Trump as “the most openly corrupt president in American history”. The irony, as Bregman put it, is that the lecture was precisely about “the paralysing cowardice of today’s elites”. When even the BBC flinches from stating the obvious – and presumably fears how Trump might react (he has threatened to sue the broadcaster for $5 billion over doctored footage that, earlier in November, saw the director general and News CEO resign) – you know something is deeply rotten.

Bregman’s opening lecture is well worth a listen, as is the Q&A afterwards. His strong opinions chimed with the beliefs of Gemma Milne, a Scottish science writer and lecturer at the University of Glasgow, whom I caught up with a couple of weeks ago, having first interviewed her almost a decade ago.

The author of Smoke & Mirrors: How Hype Obscures the Future and How to See Past It has recently submitted her PhD thesis at the University of Edinburgh (Putting the future to work – The promises, product, and practices of corporate futurism), and has been tracking this shift for years. Her research focuses on “corporate futurism” and the political economy of deep tech – essentially, who benefits from the stories we tell about innovation.

Her analysis is blunt: we’re living through what she calls “the age of badness”.

“Culturally, we have peaks and troughs in terms of how much ‘badness’ is tolerated,” she told me. “Right now, being the bad guy is not just accepted, it’s actually quite cool. Look at Elon Musk, Trump, and Peter Thiel. There’s a pragmatist bent that says: the world is what it is, you just have to operate in it.”

When Smoke and Mirrors came out in 2020, conversations around responsible innovation were easier. Entrepreneurs genuinely wanted to get it right. The mood has since curdled. “If hype is how you get things done and people get misled along the way, so be it,” Gemma said of the evolved attitude by those in power. “‘The ends justify the means’ has become the prevailing logic.”

On a not-unrelated note, November 30 marked exactly three years since OpenAI launched ChatGPT. (This end-of-the-month newsletter arrives a day later than usual – the weekend, plus an embargo on the Adaptavist Group research below.) We’ve endured three years of breathless proclamations about productivity gains, creative disruption, and the democratisation of intelligence. And three years of pilot programmes, failed implementations, and so much hype.

Meanwhile, the graduate job market has collapsed by two-thirds in the UK alone, and unemployment levels have risen to 5%, the highest since September 2021, the height of the pandemic fallout, as confirmed by Office for National Statistics data published in mid-November.

New research from The Adaptavist Group, gleaned from almost 5,000 knowledge workers split evenly across the UK, US, Canada and Germany, underscores the insidious social cost: a third (32%) of workers report speaking to colleagues less since using GenAI, and 26% would rather engage in small talk with an AI chatbot than with a human.

So here’s the question that Bregman forces us to confront: if we now have access to more intelligence than ever before – both human and artificial – what exactly are we doing with it? And are we using technology for good, for human enrichment and flourishing? On the whole, with artificial intelligence, I don’t think so.

Bregman describes consultancy, finance, and corporate law as a “gaping black hole” that sucks up brilliant minds: a Bermuda Triangle of talent that has tripled in size since the 1980s. Every year, he notes, thousands of teenagers write beautiful university application essays about solving climate change, curing disease, or ending poverty. A few years later, most have been funnelled towards the likes of McKinsey, Goldman Sachs, and Magic Circle law firms.

The numbers bear this out. Around 40% of Harvard graduates now end up in that Bermuda Triangle of talent, according to Bregman. Include big tech, and the share rises above 60%. One Facebook employee, a former maths prodigy, quoted by the Dutchman in his first Reith lecture, said: “The best minds of my generation are thinking about how to make people click ads. That sucks.”

If we’ve spent decades optimising our brightest minds towards rent-seeking and attention-harvesting, AI accelerates that trajectory. The same tools that could solve genuine problems are instead deployed to make advertising more addictive, to automate entry-level jobs without creating pathways to replace them, and to generate endless content that says nothing new.

Gemma sees this in how technology and politics have fused. “The entanglement has never been stronger or more explicit.” Twelve months ago, Trump won the vote for his second term. At his inauguration at the White House in January, the front-row seats were taken by several technology leaders, happy to pay the price for genuflection in return for deregulation. But what is the ultimate cost to humanity for having such cosy relationships?

“These connections aren’t just more visible, they’re culturally embedded,” Gemma told me. “People know Musk’s name and face without understanding Tesla’s technology. Sam Altman is AI’s hype guru, but he’s also a political leader now. The two roles have merged.”

Against this backdrop, I spent two days at London’s Guildhall in early November for the Thinkers50 conference and gala. The theme was “regeneration”, exploring whether businesses can restore rather than extract.

Erinch Sahan from Doughnut Economics Action Lab offered concrete, heartwarming examples of businesses demonstrating that purpose and profit needn’t be mutually exclusive. For instance, Patagonia’s steward ownership model, Fairphone’s “most ethical smartphone in the world” with modular repairability, and LUSH’s commitment to fair taxes and employee ownership.

Erinch’s – frankly heartwarming – list, of which this trio is a small fraction, contrasted sharply with Gemma’s observation about corporate futurism: “The critical question is whether it actually transforms organisations or simply attends to the fear of perma-crisis. You bring in consultants, do the exercises, and everyone feels better about uncertainty. But does anything actually change?”

Some forms of the practice can be transformative. Others primarily manage emotion without producing radical change. The difference lies in whether accountability mechanisms exist, whether outcomes are measured, tracked, and tied to consequences.

This brings me to Delhi-based Ruchi Gupta, whom I met over a video call a few weeks ago. She runs the not-for-profit Future of India Foundation and has built something that embodies precisely the kind of “moral ambition” Bregman describes, although she’d probably never use that phrase.

India is home to the world’s largest youth population, with one in every five young people globally being Indian. Not many – and not enough – are afforded the skills and opportunities to thrive. Ruchi’s assessment of the current situation is unflinching. “It’s dire,” she said. “We have the world’s largest youth population, but insufficient jobs. The education system isn’t skilling them properly; even among the 27% who attend college, many graduate without marketable skills or professional socialisation. Young people will approach you and simply blurt things out without introducing themselves. They don’t have the sophistication or the networks.”

Notably, cities comprise just 3% of India’s land area but account for 60% of India’s GDP. That concentration tells you everything about how poorly opportunities are distributed.

Gupta’s flagship initiative, YouthPOWER, responds to this demographic reality by creating India’s first and only district-level youth opportunity and accountability platform, covering all 800 districts. The platform synthesises data from 21 government sources to generate the Y-POWER Score, a composite metric designed to make youth opportunity visible, comparable, and politically actionable.

“Approximately 85% of Indians continue to live in the district of their birth,” Ruchi explained. “That’s where they situate their identity; when young people introduce themselves to me, they say their name and their district. If you want to reach all young people and create genuine opportunities, it has to happen at the district level. Yet nothing existed to map opportunity at that granularity.”

What makes YouthPOWER remarkable, aside from the smart data aggregation, is the accountability mechanism. Each district is mapped to its local elected representative, the Member of Parliament who chairs the district oversight committee. The platform creates a feedback loop between outcomes and political responsibility.

“Data alone is insufficient; you need forward motion,” Ruchi said. “We mapped each district to its MP. The idea is to work directly with them, run pilots that demonstrate tangible improvement, then scale a proven playbook across all 543 constituencies. When outcomes are linked to specific politicians, accountability becomes real rather than rhetorical.”

Her background illuminates why this matters personally. Despite attending good schools in Delhi, her family’s circumstances meant she didn’t know about premier networking institutions. She went to an American university because it let her work while studying, not because it was the best fit. She applied only to Harvard Business School, having learnt about it from Eric Segal’s Love Story, without any work experience.

“Your background determines which opportunities you even know exist,” she told me. “It was only at McKinsey that I finally understood what a network does – the things that happen when you can simply pick up the phone and reach someone.” Thankfully, for India’s sake, Ruchi has found her purpose after time spent lost in the Bermuda Triangle of talent.

But the lack of opportunities and woeful political accountability are global challenges. Ruchi continued: “The right-wing surge you’re seeing in the UK and the US stems from the same problem: opportunity isn’t reaching people where they live. The normative framework is universal: education, skilling, and jobs on one side; empirical baselines and accountability mechanisms on the other. Link outcomes to elected representatives, and you create a feedback loop that drives improvement.”

So what distinguishes genuine technology for good from its performative alternative?

Gemma’s advice is to be explicit about your relationship with hype. “Treat it like your relationship with money. Some people find money distasteful but necessary; others strategise around it obsessively. Hype works the same way. It’s fundamentally about persuasion and attention, getting people to stop and listen. In an attention economy, recognising how you use hype is essential for making ethical and pragmatic decisions.”

She doesn’t believe we’ll stay in the age of badness forever. These things are cyclical. Responsible innovation will become fashionable again. But right now, critiquing hype lands very differently because the response is simply: “Well, we have to hype. How else do you get things done?”

Ruchi offers a different lens. The economist Joel Mokyr has demonstrated that innovation is fundamentally about culture, not just human capital or resources. “Our greatness in India will depend on whether we can build that culture of innovation,” Ruchi said. “We can’t simply skill people as coders and rely on labour arbitrage. That’s the current model, and it’s insufficient. If we want to be a genuinely great country, we need to pivot towards something more ambitious.”

Three years into the ChatGPT era, we have a choice. We can continue funnelling talent into the Bermuda Triangle, using AI to amplify artificial importance. Or we can build something different. For instance, pioneering accountability systems like YouthPOWER that make opportunity visible, governance structures that demand transparency, and cultures that invite people to contribute to something larger than themselves.

Bregman ends his opening Reith Lecture with a simple observation: moral revolutions happen when people are asked to participate.

Perhaps that’s the most important thing leaders can do in 2026: not buy more AI subscriptions or launch more pilots. But ask the question: what ladder are we climbing, and who benefits when we reach the top?

The present

Image created on Midjourney

The other Tuesday, on the 8.20am train from Waterloo to Clapham Junction, heading to The Portfolio Collective’s Portfolio Career Festival at Battersea Arts Centre, I witnessed a small moment that captured everything wrong with how we’re approaching AI.

The guard announced himself over the tannoy. But it wasn’t his (or her) voice. It was a robotic, AI-generated monotone informing passengers he was in coach six, should anyone need him.

I sat there, genuinely unnerved. This was the Turing trap in action, using technology to imitate humans rather than augment them. The guard had every opportunity to show his character, his personality, perhaps a bit of warmth on a grey November morning. Instead, he’d outsourced the one thing that made him irreplaceable: his humanity.

Image created on Nano Banana (using the same prompt as the Midjourney one above)

Erik Brynjolfsson, the Stanford economist who coined the term in 2022, argues we consistently fall into this software snare. We design AI to mimic human capabilities rather than complement them. We play to our weaknesses – the things machines do better – instead of our strengths. The train guard’s voice was his strength. His ability to set a tone, to make passengers feel welcome, to be a human presence in a metal tube hurtling through South London. That’s precisely what got automated away.

It’s a pattern I’m seeing everywhere. By blindly grabbing AI and outsourcing tasks that reveal what makes us unique, we risk degrading human skills, eroding trust and connection, and – I say this without hyperbole – automating ourselves to extinction.

The timing of that train journey felt significant. I was heading to a festival entirely about human connection – networking, building personal brand, the importance of relationships for business and greater enrichment. And here was a live demonstration of everything working against that.

It was also Remembrance Day. As we remembered those who fought for our freedoms, not least during a two-minute silence (that felt beautifully calming – a collective, brief moment without looking at a screen), I was about to argue on stage that we’re sleepwalking into a different kind of surrender: the quiet handover of our professional autonomy to machines.

The debate – Unlocking Potential or Chasing Efficiency: AI’s Impact on Portfolio Work – was held before around 200 ambitious portfolio professionals. The question was straightforward: should we embrace AI as a tool to amplify our skills, creativity, and flow – or hand over entire workflows to autonomous agents and focus our attention elsewhere?

Pic credit: Afonso Pereira

You can guess which side I argued. The battle for humanity isn’t against machines, per se. It’s about knowing when to direct them and when to trust ourselves. It’s about recognising that the guard’s voice – warm, human, imperfect – was never a problem to be solved. It was a feature to be celebrated.

The audience wanted an honest conversation about navigating this transition thoughtfully. I hope we delivered. But stepping off stage, I couldn’t shake the irony: a festival dedicated to human connection, held on the day we honour those who preserved our freedoms, while outside these walls the evidence mounts that we’re trading professional agency for the illusion of efficiency.

To watch the full video session, please see here:

A day later, I attended an IBM panel at the tech firm’s London headquarters. Their Race for ROI research contained some encouraging news: two-thirds of UK enterprises are experiencing significant AI-driven productivity improvements. But dig beneath the headline, and the picture darkens. Only 38% of UK organisations are prioritising inclusive AI upskilling opportunities. The productivity gains are flowing to those already advantaged. Everyone else is figuring it out on their own – 77% of those using AI at work are entirely self-taught.

Leon Butler, General Manager for IBM UK & Ireland, offered a metaphor that’s stayed with me. He compared opaque AI models to drinking from an opaque test tube.

“There’s liquid in it – that’s the training data – but you can’t see it. You pour your own data in, mix it, and you’re drinking something you don’t fully understand. By the time you make decisions, you need to know it’s clean and true.”

That demand for transparency connects directly to Ruchi’s work in India and Gemma’s critique of corporate futurism. Data for good requires good data. Accountability requires visibility. You can’t build systems that serve human flourishing if the foundations are murky, biased, or simply unknown.

As Sue Daley OBE, who leads techUK’s technology and innovation work, pointed out at the IBM event: “This will be the last generation of leaders who manage only humans. Going forward, we’ll be managing humans and machines together.”

That’s true. But the more important point is this: the leaders who manage that transition well will be the ones who understand that technology is a means, not an end. Efficiency without purpose is just faster emptiness.

The question of what we’re building, and for whom, surfaced differently at the Thinkers50 conference. Lynda Gratton, whom I’ve interviewed a couple of times about living and working well, opened with her weaving metaphor. We’re all creating the cloth of our lives, she argued, from productivity threads (mastering, knowing, cooperating) and nurturing threads (friendship, intimacy, calm, adventure).

Not only is this an elegant idea, but I love the warm embrace of messiness and complexity. Life doesn’t follow a clean pattern. Threads tangle. Designs shift. The point isn’t to optimise for a single outcome but to create something textured, resilient, human.

That messiness matters more now. My recent newsletters have explored the “anti-social century” – how advances in technology correlate with increased isolation. Being in that Guildhall room – surrounded by management thinkers from around the world, having conversations over coffee, making new connections – reminded me why physical presence still matters. You can’t weave your cloth alone. You need other people’s threads intersecting with yours.

Earlier in the month, an episode of The Switch, St James’s Place Financial Adviser Academy’s career change podcast, was released. Host Gee Foottit wanted to explore how professionals can navigate AI’s impact on their working lives – the same territory I cover in this newsletter, but focused specifically on career pivots.

We talked about the six Cs – communication, creativity, compassion, courage, collaboration, and curiosity – and why these human capabilities become more valuable, not less, as routine cognitive work gets automated. We discussed how to think about AI as a tool rather than a replacement, and why the people who thrive will be those who understand when to direct machines and when to trust themselves.

The conversations I’m having – with Gemma, Ruchi, the panellists at IBM, the debaters at Battersea – reinforce the central argument. Technology for good isn’t a slogan. It’s a practice. It requires intention, accountability, and a willingness to ask uncomfortable questions about who benefits and who gets left behind.

If you’re working on something that embodies that practice – whether it’s an accountability platform, a regenerative business model, or simply a team that’s figured out how to use AI without losing its humanity – I’d love to hear from you. These conversations are what fuel the newsletter.

The past

A month ago, I fired my one and only work colleague. It was the best decision for both of us. But the office still feels lonely and quiet without him.

Frank is a Jack Russell I’ve had since he was a puppy, almost five years ago. My daughter, only six months old when he came into our lives, grew up with him. Many people with whom I’ve had video calls will know Frank – especially if the doorbell went off during our meeting. He was the most loyal and loving dog, and for weeks after he left, I felt bereft. Suddenly, no one was nudging me in the middle of the afternoon to go for a much-needed, head-clearing stroll around the park.

Pic credit: Samer Moukarzel

So why did I rehome him?

As a Jack Russell, he is fiercely territorial. And where I live and work in south-east London, it’s busy. He was always on guard, trying to protect and serve me. The postman, Pieter, various delivery folk, and other people who came into the house have felt his presence, let’s say. Countless letters were torn to shreds by his vicious teeth – so many that I had to install an external letterbox.

A couple of months ago, while trying to retrieve a sock that Frank had stolen and was guarding on the sofa, he snapped and drew blood. After multiple sessions with two different behaviourists, following previous incidents, he was already on a yellow card. If he bit me, who wouldn’t he bite? Red card.

The decision was made to find a new owner. I made a three-hour round trip to meet Frank’s new family, whose home is in the Norfolk countryside – much better suited to a Jack Russell’s temperament. After a walk together in a neutral venue, he travelled back to their house and apparently took 45 minutes to leave their car, snarling, unsure, and confused. It was heartbreaking to think he would never see me again.

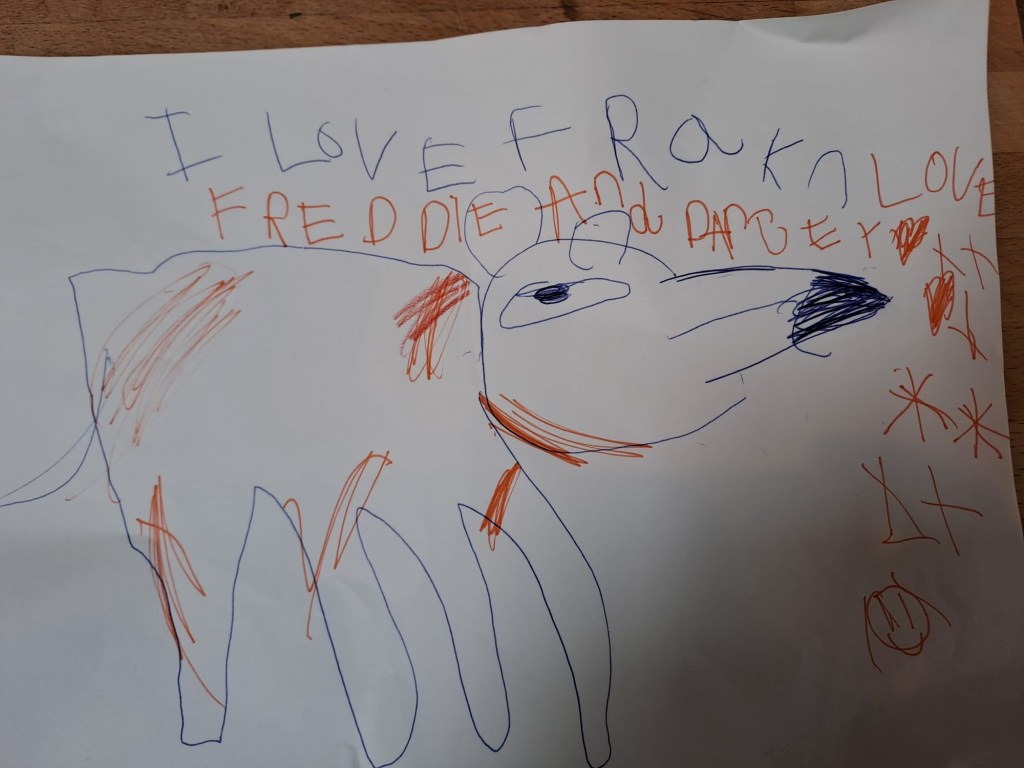

But I knew Frank would be happy there. Later that day, I received videos of him dashing around fields. His new owners said they already loved him. A day later, they found the cartoon picture my daughter had drawn of Frank, saying she loved him, in the bag of stuff I’d handed them.

Now, almost a month on, the house is calmer. My daughter has stopped drawing pictures of Frank with tearful captions. And Frank? He’s made friends with Ralph, the black Labrador who shares his new home. The latest photo shows them sleeping side by side, exhausted from whatever countryside adventures Jack Russells and Labradors get up to together.

The proverb “if you love someone, set them free” helped ease the hurt. But there’s something else in this small domestic drama that connects to everything I’ve been writing about this month.

Bregman asks what ladder we’re climbing. Gemma describes an age where doing the wrong thing has become culturally acceptable. Ruchi builds systems that create accountability where none existed. And here I was, facing a much smaller question: what do I owe this dog?

The easy path was to keep him. To manage the risk, install more barriers, and hope for the best. The more challenging path was to acknowledge that the situation wasn’t working – not for him, not for us – and to make a change that felt like failure but was actually responsibility.

Moral ambition doesn’t only show up in accountability platforms and regenerative business models. Sometimes it’s in the quiet decisions: the ones that cost you something, that nobody else sees, that you make because it’s right rather than because it’s easy.

Frank needed space to run, another dog to play with, and owners who could give him the environment his breed demands. I couldn’t provide that. Pretending otherwise would have been a disservice to him and a risk to my family.

The age of badness that Gemma describes isn’t just about billionaires and politicians. It’s also about the small surrenders we make every day: the moments we choose convenience over responsibility, comfort over honesty, the path of least resistance over the path that’s actually right.

I don’t want to overstate this. Rehoming a dog is not the same as building YouthPOWER or challenging tax-avoiding elites at Davos. But the muscle is the same. The willingness to ask uncomfortable questions. The courage to act on the answers.

My daughter’s drawings have stopped. The house is quieter. And somewhere in Norfolk, Frank is sleeping on a Labrador, finally at peace.

Sometimes the most important thing you can do is recognise when you’re climbing the wrong ladder – and have the grace to climb down.

Statistics of the month

🛒 Cyber Monday breaks records

Today marks the 20th annual Cyber Monday, projected to hit $14.2 billion in US sales – surpassing last year’s record. Peak spending occurs between 8pm and 10pm, when consumers spend roughly $15.8 million per minute. A reminder that convenience still trumps almost everything. (National Retail Federation)

🎯 Judgment holds, execution collapses

US marketing job postings dropped 8% overall in 2025, but the divide is stark: writer roles fell 28%, computer graphic artists dropped 33%, while creative directors held steady. The pattern likely mirrors the UK – the market pays for strategic judgment; it’s automating production. (Bloomberry)

🛡️ Cybersecurity complacency exposed

Nearly half (43%) of UK organisations believe their cybersecurity strategy requires little to no improvement – yet 71% have paid a ransom in the past 12 months, averaging £1.05 million per payment. (Cohesity)

💸 Cyber insurance claims triple

UK cyber insurance claims hit at least £197 million in 2024, up from £60 million the previous year – a stark reminder that threats are evolving faster than our defences. (Association of British Insurers)

🤖 UK leads Europe in AI optimism

Some 88% of UK IT professionals want more automation in their day-to-day work, and only 10% feel AI threatens their role – the lowest of any European country surveyed. Yet 26% say they need better AI training to keep pace. (TOPdesk)

Thank you for reading Go Flux Yourself. Subscribe for free to receive this monthly newsletter straight to your inbox.

All feedback is welcome, via oliver@pickup.media. If you enjoyed reading, pass it on! Please consider sharing it via social media or email. Thank you.

And if you are interested in my writing, speaking and strategising services, you can find me on LinkedIn or email me using oliver@pickup.media.