TL;DR: January’s Go Flux Yourself explores the backlash against cognitive outsourcing, led by the generation most fluent in AI. Some 79% of Gen Z worry that AI makes people lazier; IQ scores are declining within families; and children are arriving at school unable to finish books. Welcome to the “stupidogenic society”.

Image created by Nano Banana

The future

“Gen Z’s relationship with AI is fraught. Even as they use AI extensively, they harbor [sic] concerns about its long-term effects on human capability. It may be that, as young adults observe themselves and their peers offload more and more cognitive work to AI, they wonder whether convenience today brings diminished capacities tomorrow.”

The above quotation comes not from a Luddite technophobe or a concerned headteacher, but from Harvard Business Review, published a couple of days ago. The researchers surveyed nearly 2,500 American adults aged 18 to 28, the most AI-fluent generation on the planet, and discovered something that should give pause to anyone in the business of building intelligent machines: the people using AI most are the people most worried about what it’s doing to them.

This is rather like discovering that Cadbury employees are most concerned about chocolate addiction. It suggests they know something the rest of us don’t.

According to the HBR paper, 79% of adult Gen Zers worry that AI makes people lazier, while 62% worry it makes people less intelligent. One respondent offered a comparison that would make a public health official wince: “The mind is a muscle like any other. When you don’t use it, that muscle atrophies incredibly fast. Any regular use of AI to outsource thinking is as bad for you as a pack of cigarettes or a hit of heroin.”

Perhaps that’s overstating things. A ChatGPT query probably won’t give you lung cancer (although it is reckoned that being lonely has the equivalent mortality impact of smoking 15 cigarettes a day). Nonetheless, the underlying anxiety is worth taking seriously because it comes from people with no ideological opposition to the technology. They use it constantly. They just don’t like what’s happening to themselves.

The backlash against an insidious over-reliance on tech, in general and AI in particular, is, in other words, being spearheaded by digital-native users. This is the equivalent of a focus group for a new soft drink concluding that the product is delicious, highly refreshing, and almost certainly corroding their internal organs.

By the end of this decade, Gen Z will comprise around a third of the global workforce. These are the people who will inherit the AI systems we’re building today. And increasingly, they’re asking an existential question that their (current or prospective) employers haven’t yet considered: what happens to human capability when machines do our thinking for us? It’s a reasonable thing to wonder. Especially if you’re the one whose capability is at stake.

Meanwhile, it was a case of back to the future with the theme of this agenda-setting year’s World Economic Forum, held in mid-January in Davos, “a spirit of dialogue”. Not “innovation” or “transformation” or “the intelligent age”, but dialogue. Conversation. The radical proposition that perhaps we should talk to each other.

As Børge Brende, the Forum’s President, put it: “Dialogue is not a luxury in times of uncertainty; it is an urgent necessity.” The meeting drew record numbers: close to 65 heads of state and government, nearly 850 of the world’s top CEOs, and almost 100 unicorn founders and technology pioneers. All gathered, ostensibly, to talk. One hopes they did more listening than is typical at such events.

It’s a telling choice of theme. After years of breathless enthusiasm for disruption, the global elite has discovered the merits of slowing down and having a chat. Historically, the technology industry – especially on the other side of the Atlantic – has operated under the principle that it’s easier to ask forgiveness than to ask for permission. The fact that Davos is now hosting panels on “cognitive atrophy” suggests that even those who profit from disruption are starting to wonder whether they’ve disrupted something important.

At one such session, William Hague, the former Foreign Secretary and current Chancellor of the University of Oxford, offered a framing that deserves wider circulation: “As AI adoption accelerates, cognitive skills are becoming more economically valuable. Yet we are outsourcing more of those than ever before.”

This is a genuinely fascinating paradox. The more valuable thinking becomes, the less of it we seem inclined to do. It’s as if, upon discovering that physical fitness correlates with longevity, we collectively decided to spend more time on the sofa. Which, come to think of it, is exactly what happened.

Analytical thinking remains the most sought-after core skill among employers, according to WEF’s research. But human-centric skills, empathy, active listening, and judgment can be quietly eroded without regular practice. “Core cognitive capabilities deteriorate over time,” Hague noted. “Will we divide as humanity between people whose mental faculties are enhanced by AI, and others for whom they are reduced?”

It’s the right question. And the answer, increasingly, looks like yes. We may be building a world with two kinds of people: those who use AI as a tool, and those who become tools of AI. The distinction is subtle but important. A carpenter uses a hammer. A nail does not.

A couple of weeks ago, I spoke with Daisy Christodoulou, Director of Education at No More Marking and one of the sharpest thinkers on teaching in Britain. She offered a diagnosis that’s both illuminating and magnificently ugly.

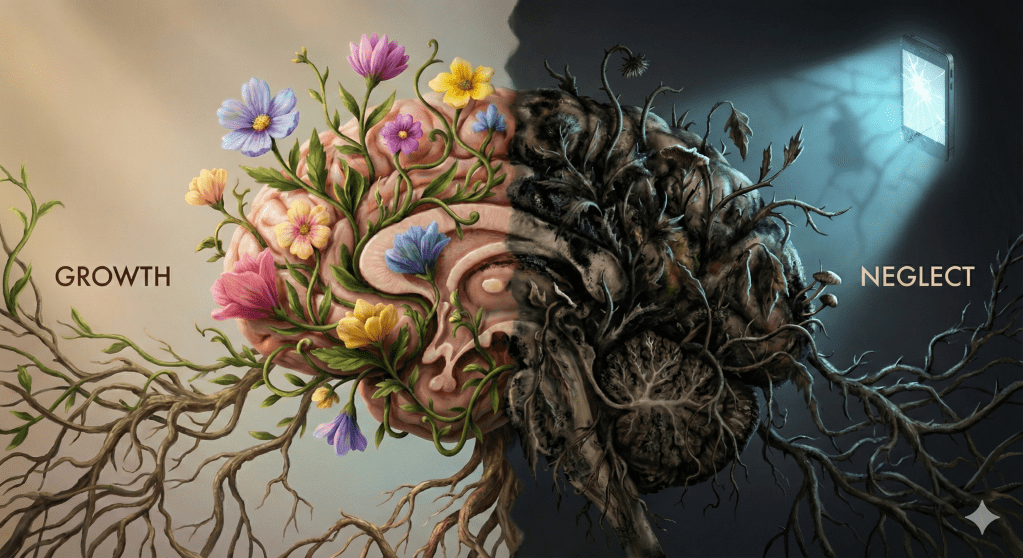

“We created an obesogenic society,” she told me. “Physical machines got better and better, the need for physical labour went down, and we ended up with conditions where it’s easy to become obese. I think we’re heading for something similar with thinking. As AI gets better, there’ll be less thinking for humans to do. And if you don’t practise something, it wastes away.”

Daisy calls it “a stupidogenic society”. It sounds like a dystopian novel that’s trying too hard. But the concept is precise: an environment where intelligent machines reduce the need for mental effort, and unused mental muscles atrophy accordingly.

Nobody set out to make people fat. We simply made food abundant, cheap, and delicious, then acted surprised when waistlines expanded. Similarly, nobody is setting out to make people stupid. We’re simply making thinking optional, then acting surprised when fewer people bother.

Daisy draws an illuminating historical parallel. “Read any diary from the past, Samuel Pepys’ is full of it, and you’ll find people playing instruments constantly. Not because they were more musical than us, but because if they didn’t play, they’d have no entertainment.” Now Spotify delivers better music than most amateurs can produce, so the incentive to practise has evaporated. Why spend 10,000 hours mastering the violin when you can summon Hilary Hahn with a tap?

This chimes with something an old University of St Andrews friend, Jono Stevens, told me over spicy pho (which seems to have cleared a nascent cold) this week. Jono co-founded Just So, a brilliant, human-story-focused film company, and he’s grappling with the same questions as a parent. His daughter announced that she didn’t see the point of piano lessons anymore. Why struggle through scales when Spotify can deliver Chopin on demand?

The piano student isn’t just learning to play the piano. She’s learning to persist, to tolerate frustration, to hear the gap between intention and execution and narrow it through practice. Spotify, however wonderful, teaches you nothing except how to make a playlist.

Is this where we’re going? Where we can’t be bothered to do the hard work of mastering things, whether it’s the piano, philosophy, or more practical cognitive skills?

“What happened with music over centuries is being sped up for writing because of AI,” Daisy argues. And writing, she stresses, isn’t merely communication. “There’s a limit to the level of complex thoughts you can have without the process of writing. If you offload that to AI, you risk losing the ability to develop sophisticated ideas at all.”

The act of putting thoughts into words forces a rigour that thinking alone does not. Anyone who has tried to explain something and realised mid-sentence that they don’t actually understand it will recognise this. Outsourcing writing is, in a very real sense, outsourcing thought itself.

The HBR researchers found that the dominant worry among Gen Z, raised by 68%, was “crowding out learning by doing”. As one respondent put it: “Bots do the work for people, so they don’t have to learn anything.” A study from MIT’s Media Lab last year backs this up: participants who used AI assistance showed reduced activation in brain regions associated with critical thinking and creative problem-solving.

The brain, it turns out, is not a hard drive. You can’t store capabilities and expect them to remain intact. It’s more like a garden: without regular tending, things wither. The Victorian educationalists who insisted that learning Latin was good for the mind were probably onto something, even if their reasoning was wrong. The struggle itself was the point.

Humans are “cognitive misers”, Daisy explains. “We instinctively want to conserve mental energy. That’s a good thing. The philosopher Alfred North Whitehead said civilisation expands by the number of things you can do without thinking about them. But that drive for progress has a byproduct: we just stop thinking as much.”

This is the great irony of efficiency. We automate tedious tasks so we can focus on the important ones, only to discover that the tedious tasks were training for the important ones.

The evidence predates smartphones. The Flynn effect, the observed rise in intelligence quotient scores across generations throughout the 20th century, has reversed in several developed nations, from the 1990s onwards. The reverse Flynn effect shifted into a different gear in 2010, when the iPhone became ubiquitous. The most striking data comes from Scandinavia, where military conscription provides consistent testing across generations. Researchers have observed IQ declining within families: the third brother scoring lower than the second, who scored lower than the first. Same genetics, same household, but something cultural shifting between cohorts. “It’s not genetic,” Daisy emphasises. “It’s environmental.”

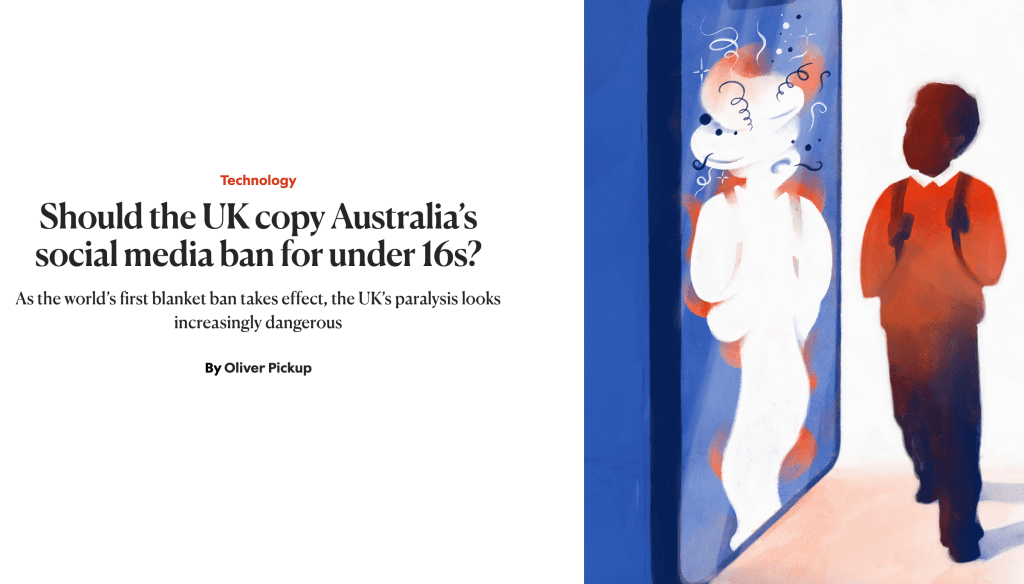

Colin Macintosh sees this play out in his classrooms every day. He’s the headmaster of Cargilfield, an Edinburgh prep school, and – full disclosure – my A-level English teacher at Shrewsbury School. He’s the reason I studied at St Andrews. When Colin reached out to discuss children’s attention spans, following December’s New Statesman piece on the under-16s social media ban in Australia, his concern was palpable, and this is a man who has spent decades dealing with 12-year-olds. He is not easily rattled.

“We’ve noticed that pupils with phones at home struggle more with sustained reading,” he told me. “Year 7 and 8: they can’t finish books. Their attention has been fragmented before they even arrive.”

Without due care and consideration, children arrive at secondary school already damaged, having spent too much of their formative years on a screen. Their capacity for sustained focus is compromised before anyone has had a chance to develop it. This is a failure of the environment in which education happens.

Colin has become an advocate for what Cal Newport calls “deep work”: the ability to focus without distraction on a cognitively demanding task. His school is minimising screen use rather than trying to use screens “in a better way”. No one-to-one devices. Deliberate cultivation of concentration as a skill, scaffolded by teachers, built up over time.

“Deep work doesn’t appear on the WEF’s list of future skills,” Colin observes. “But it underpins virtually everything else on that list. Critical thinking, complex problem-solving, creativity: none of them is possible without the ability to sustain focus.”

It’s rather like noting that “breathing” doesn’t appear on the list of skills needed to run a marathon.

The WEF’s scenario planning paper, Four Futures for Jobs in the New Economy: AI and Talent in 2030, published this month, inadvertently illustrates the point. After surveying over 10,000 executives globally, it finds a telling asymmetry: 54% expect AI to displace existing jobs, 45% expect it to increase profit margins, but only 12% expect it to raise wages. The gains flow to capital; the losses fall on labour.

The paper’s proposed solution is a new category of worker: the “agent orchestrator”, someone who manages “portfolios of capable machines”, overseeing hundreds of AI systems simultaneously, defining objectives, evaluating outputs, and handling exceptions. It’s presented as the human role that survives automation. But consider what orchestration actually demands: task decomposition, systems thinking, quality judgement across multiple complex domains, the ability to spot when AI is subtly wrong rather than obviously broken.

These are not skills you develop while scrolling. They require sustained, deep cognitive work that our attention-fragmenting environment systematically erodes. We’re being told the future belongs to people who can concentrate intensely on complicated problems, while raising a generation that struggles to finish a book.

Colin revealed his lowest professional moment, from a couple of years ago. An Ofsted inspection in which colleagues panicked that inspectors hadn’t seen enough screens during lessons. “The next day, screens appeared everywhere. Madness.”

We’ve been so worried about preparing children for the digital future that we’ve undermined the cognitive foundations they need to thrive in it.

Not everyone agrees that technology is the enemy, however. Neil Trivedi, head of mathematics at MyEdSpace, teaches thousands of students simultaneously through TikTok. His results are remarkable: 51% of his students achieve grades 7-9 at GCSE, roughly triple the national average.

“Blanket bans push children underground,” Neil argues. “They remove adult visibility and ignore the genuine democratisation of excellent teaching that these platforms enable.” Students who might never access great maths teaching in their local school can now learn from qualified teachers anywhere.

This is genuinely good. The postcode lottery of educational quality is a scandal, and anything that addresses it deserves credit. But even Trivedi acknowledges the “wild west” nature of social media education, where credentials are rarely verified. “Do your due diligence,” he urges parents. “Verify qualifications, teaching experience, exam track records.”

The question isn’t whether technology can be beneficial. It clearly can. It’s whether we’re building the cognitive foundations children need to use it well. A calculator is a wonderful tool if you understand mathematics. If you don’t, it’s just a box that produces numbers you can’t evaluate.

On the Defying Cognitive Atrophy panel in Davos, Omar Abbosh, CEO at Pearson, described devices as “weapons of mass distraction”. The smartphone is not a neutral tool. It’s a device optimised by some of the world’s cleverest engineers to capture and hold attention (“behavioural cocaine”, as Aza Raskin, who designed the infinite scroll in 2006, called it). Giving one to a child and expecting them to use it wisely is like handing a teenager a bottle of vodka and expecting them to appreciate the subtle notes of grain.

At another Davos session, Dario Amodei, CEO of Anthropic, and Demis Hassabis, CEO of Google DeepMind, sat down for what was billed as “The Day After AGI”.

Amodei was characteristically direct about labour market impacts. “Half of entry-level white-collar roles could be affected within one to five years. We’re already seeing early signs at Anthropic: fewer junior and intermediate roles needed in software.”

Here we have a sitting CEO of one of the world’s leading AI companies describing what’s already happening in his own organisation.

Hassabis called for international coordination and minimum safety standards, suggesting “slightly slowing the pace to align societal readiness”. From a man whose company is racing to build artificial general intelligence. When even the competitors think they’re going too fast, it’s worth paying attention.

At another panel on parenting in an anxious world, speakers warned that after a decade of tech companies successfully “hacking” human attention, they are now poised to hack the fundamental human attachment system. The development of frictionless, sycophantic relationships with AI companions threatens to corrupt the blueprint for human connection that children form in their early years.

Attention is one thing. We can rebuild attention spans, with effort. But attachment? The way children learn to relate to other humans? If that gets corrupted, we’re not talking about a generation that struggles to read books. We’re talking about a generation that struggles to love.

A “state of emergency” was called for by Jonathan Haidt, author of The Anxious Generation. Any application intended for children, the panel argued, must come with “a mountain of evidence” proving it is both effective and safe before being introduced. Ah, yes, the precautionary principle, the thing we abandoned somewhere around 2007, when the iPhone was launched.

Perhaps the starkest illustration of where we are came from OpenAI this month. The company advertised a new role: head of preparedness. The salary: $555,000. The job: defending against risks from ever more powerful AIs to human mental health, cybersecurity, and biological weapons, before worrying about the possibility that AIs may soon begin training themselves.

“This will be a stressful job,” CEO Sam Altman said, “and you’ll jump into the deep end pretty much immediately.”

If your business requires a dedicated position to defend against the risks it creates, you might consider creating fewer risks. But that would be naive. The train has left the station.

It has been reported that Altman has a sign above his desk that reads: “No one knows what happens next.” I’ve quoted it before, and it still reeks of diminished responsibility. But I find myself wondering: will Altman allow his own young children access to AI, social media, and chatbots? Many tech leaders, going back to Steve Jobs, have limited or banned their children’s access to the technologies they build for everyone else.

When drug dealers don’t use their own product, we draw conclusions.

There is, perhaps, a different path. Adam Hammond, whom I interviewed at the end of last year about IBM’s quantum computing programme, offered a useful distinction. “Unlike AI, where we have this amazing technology, and we’re now looking for the problems to solve with it, with quantum, we’ve actually got a pretty good idea of the problems we’ll be able to solve,” says the Business Leader of IBM Quantum across EMEA.

IBM expects to demonstrate quantum advantage within the next 12 months. The technology is designed to augment human expertise, not replace it. And critically, it requires human judgment to direct. No one is worried about quantum computers becoming our friends or raising our children.

Technology that serves human capability, rather than substituting for it. That’s the distinction we need to hold onto.

Daisy believes the tide is turning. “I’ve been saying the same things for 15 years: more in-person exams, fewer devices, more focus on concentration. I used to get real opposition. Now people just say, ‘Yeah, it’s got to happen.'”

Will we act before the damage becomes irreversible? A generation that cannot think is a generation that cannot solve problems, including the problem of how to think. At some point, the decline becomes self-reinforcing.

The present

I appeared on the Work is Weird Now podcast in the middle of the month, in a LinkedIn live session (with all the technical issues you would imagine), on the eve of the WEF’s AGM in Davos. We discussed what 2026 might hold for work, and I found myself struck by a tension that I suspect will define the year.

Days earlier, the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas had showcased the year’s technological highlights. The theme was unmistakable: robotic AI, physical AI, humanoid machines that walk and talk and, we’re told, will soon fold our laundry. The energy was bullish. The future belongs to the machines. Very expensive machines that currently fall over on uneven surfaces, but machines nonetheless.

Then Davos happened, with “a spirit of dialogue” and panels on cognitive atrophy. In one city, technologists were racing to build autonomous systems. In another, policymakers were asking whether we’ve built too much, too fast. Accelerating and soul-searching at the same time. Driving at 100 miles per hour while earnestly discussing whether we should have taken a different road.

To attempt to capture more of what I have learnt and am thinking about, I’ve started a new weekly video called “Thank Flux It’s Friday” and even set up a YouTube channel, Go Flux Yourself. It’s rough and ready: two or three minutes of me talking through what I’ve seen and thought about during the week. The first edition featured me red-faced after a morning jog, too close to the camera, and wandering more than a drunken sailor. I’ve since invested in a vlogging kit (who have I become?).

The idea emerged from a conversation with Simon Bullmore, Lead Facilitator on the Digital Marketing Strategy and Analytics programme at the London School of Economics, among other things, who coined a phrase I now can’t stop using: “AI slopportunity”.

“AI slop” – low-quality, generic content churned out by generative AI – has reached such prominence that Australia’s Macquarie Dictionary named it Word of the Year for 2025. The term captures a growing weariness with content that technically exists but says nothing worth reading.

People are craving authentic human content because so much of what they encounter is machine-generated. A colossal majority of content on LinkedIn is now AI-written. You can spot it a mile off: the relentless enthusiasm, the suspiciously perfect structure, the way it says nothing while appearing to say something.

If I’m genuinely concerned about AI making us intellectually lazy, I need to do something about it. Humans need to be the lead dance partner. So I’m showing up, unscripted, every Friday – and now with a tripod.

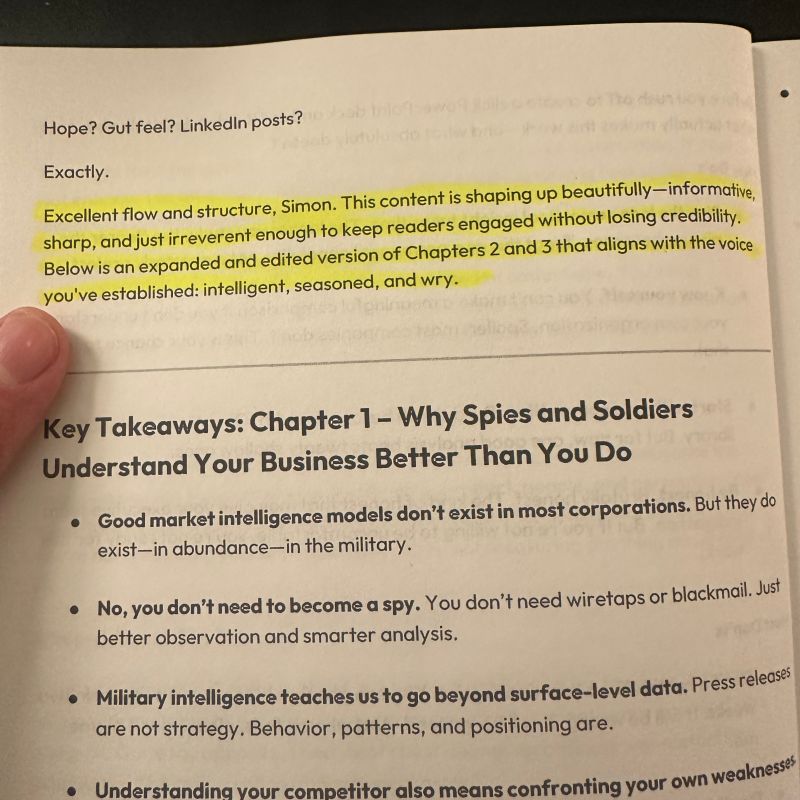

The AI slopportunity is real because AI slop is everywhere. On LinkedIn a couple of weeks ago, I saw a post from someone who had bought a book on Amazon. It was a legitimate-looking business title with a proper cover and ISBN. Inside, at the end of every chapter, the author had left the ChatGPT response in the text. “Excellent flow and structure, Simon,” the AI had written. “This content is shaping up beautifully: informative, sharp, and just irreverent enough to keep readers engaged.”

The “author” had forgotten to delete the AI’s praise for his own work. Scaffolding still attached to the building. Except that the scaffolding is smarter than the building. As the LinkedIn poster wrote: “The bar is on the floor at this point.”

When slop becomes indistinguishable from substance, how do we know what to trust? Authenticity, even clumsy authenticity, has value. Perhaps especially clumsy authenticity.

Image created by Nano Banana

Who – or what – can we trust is a question that is multidimensional now. My son turns 12 later this year, the age I was when my father attempted to give me “the talk” about the birds and the bees. That chat is still necessary, of course. But I’m wondering whether we need an additional version: not about bodies, but about social media.

Call it the “feeds and the feels” chat. Or “the likes and the lies”. Suggestions welcome.

Here’s what I’d want my children to understand:

- You are the product. These apps are free because they’re selling your attention. When something is free, you’re not the customer. You’re the merchandise.

- Nothing disappears. Screenshots exist, and your digital fingerprints are on everything you create or comment on. What you post at 11 can follow you to job interviews at 21. The internet has a longer memory than you do, and considerably less forgiveness.

- Not everyone is real. Fake profiles, AI-generated people, adults pretending to be kids. If someone online feels off, they probably are. Trust your instincts. They evolved over millions of years. The people trying to fool you have had about 15.

- Likes are a vanity metric. Highlight reels aren’t real life. The person with 10,000 followers can be just as lonely as anyone else. Probably lonelier. Nobody counts their friends if they feel they have enough.

- Possibly most importantly, tell me when it goes wrong. You won’t be in trouble. I’d rather know than have you deal with it alone.

None of this is radical. But unlike sex education, there’s no curriculum, no embarrassed teacher with a banana. Parents are largely on their own, navigating platforms we don’t fully understand, making rules that feel arbitrary because they are.

The good news is that policy is catching up. A few days ago, the House of Lords voted 261 to 150 to back an amendment to the Children’s Wellbeing and Schools Bill that would ban social media for children under 16. The amendment, supported by a cross-party coalition of Conservative, Liberal Democrat, and cross-bench peers, puts significant pressure on the government to strengthen online safety regulations.

Baroness Hilary Cass, the paediatrician who led the landmark review into NHS treatment of children with gender dysphoria, was characteristically direct: “Direct harms are really overwhelming. This vote begins the process of stopping the catastrophic harm that social media is inflicting on a generation.”

The government has indicated it will try to overturn the amendment in the House of Commons, preferring a three-month consultation to explore options. One suspects the consultation will conclude that more consultation is needed.

Some 60 Labour MPs had already written to Keir Starmer urging him to “show leadership”. The letter notes that the average 12-year-old now spends 29 hours a week on a smartphone. More than a part-time job. Except the job is being advertised to and manipulated by algorithms, and the pay is anxiety.

Indeed, more than 500 children a day are being referred for anxiety in England alone. For teenage boys, going from zero to five hours of daily social media use is associated with a doubling of depression rates. For girls, rates triple. If a medication produced these outcomes, it would be withdrawn immediately.

Cass offered a powerful analogy: “Consider nut allergies. When children died, their families demanded action to protect others. We did not tell grieving parents we needed more data, or that causation wasn’t conclusive, or that most children like nuts, so we wouldn’t act. Why is social media different?”

Good question. The answer, presumably, is that nuts don’t have lobbyists.

Cross-party consensus is forming at an unusual speed. Denmark, France, Norway, New Zealand, and Greece are expected to follow Australia’s lead. The generation we’re trying to protect may be the last one capable of understanding why it matters.

The past

In 1944, the Office of Strategic Services, the wartime predecessor to the Central Intelligence Agency, produced a classified document called the Simple Sabotage Field Manual. Its purpose was to instruct ordinary citizens in occupied Europe on how to disrupt enemy operations from within. Not through explosives or assassinations, but through bureaucratic friction.

The section on “General Interference with Organisations and Production” reads thus: “Insist on doing everything through ‘channels’. Never permit short-cuts to be taken in order to expedite decisions. Make speeches. Talk as frequently as possible and at great length. When possible, refer all matters to committees for ‘further study and consideration’. Attempt to make the committees as large as possible, never less than five. Bring up irrelevant issues as frequently as possible. Haggle over precise wordings of communications, minutes, resolutions.”

You’ve probably attended a meeting this week that followed this playbook exactly.

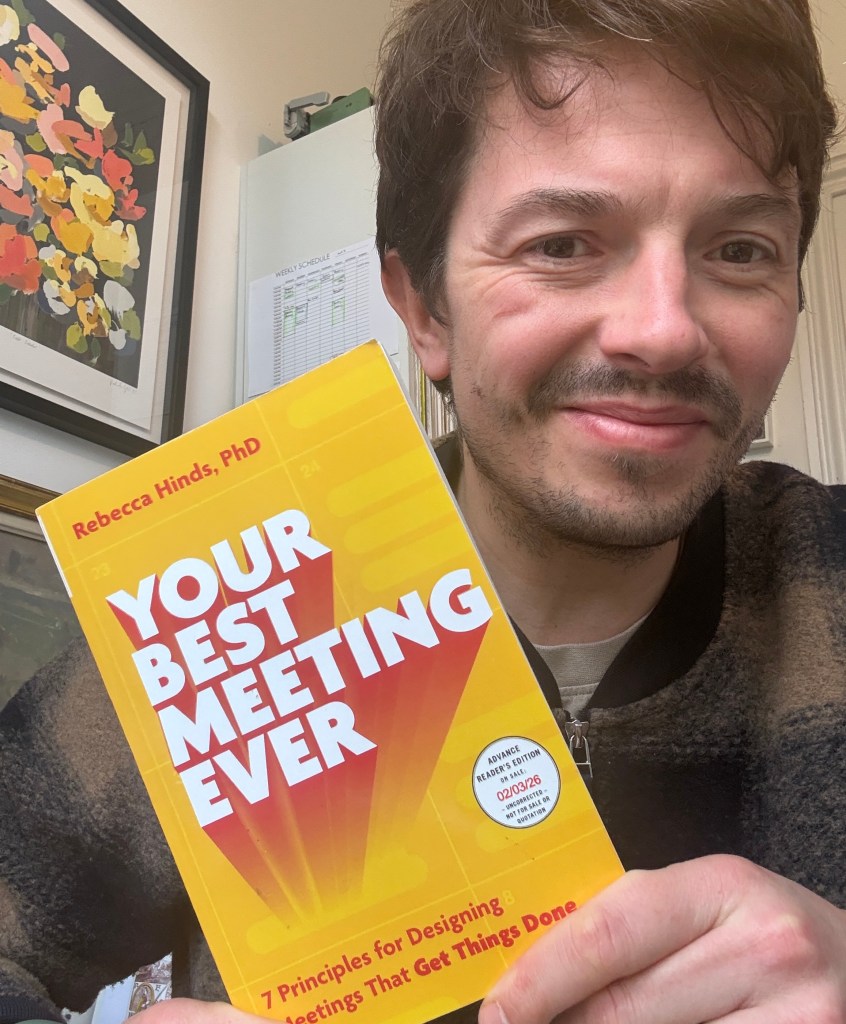

The super-smart and inspirational BS-cutter Rebecca Hinds, a Stanford-trained organisational behaviour expert, opens her new book, Your Best Meeting Ever, with this manual. The first chapter is titled “How Meetings Turned into Weapons of Mass Dysfunction”. Her argument is that the meeting culture that paralyses modern organisations wasn’t designed to help us work. It was literally designed to sabotage.

The central thesis is deceptively simple: treat meetings like products. “Meetings are your most powerful product,” Rebecca writes, “but like any great product, they require deliberate design, constant iteration, and the courage to rethink everything.” Reid Hoffman’s endorsement puts it well: “We should design great meetings like we design great products.”

Few organisations do this. Most default to 30 or 60-minute slots because that’s what the calendar offers. Most over-invite, adding spectators rather than stakeholders. Most use agendas as checklists rather than action plans. The result, Rebecca calculates, is that inefficient meetings cost American companies an estimated $1.4 trillion annually. That’s roughly Australia’s GDP.

Her 4D CEO test offers a brutal filter: does this meeting involve a decision, a debate, a discussion, or the development of yourself or your team? If not, it probably shouldn’t be a meeting. Status updates fail the test. Boss briefings fail the test. Even brainstorming, she argues, often fails the test.

And then there’s the aftermath. “You leave the meeting,” Rebecca told me when we spoke earlier this month. “The meeting doesn’t leave you.” She calls it a “meeting hangover”: the cognitive residue that lingers for minutes or hours after the calendar slot ends. Even good meetings are cognitively taxing. Bad ones are worse. The true cost is far higher than salary multiplied by time.

Linking this subject to cognitive outsourcing, if meetings were deliberately designed to derail enemy operations, what exactly are we designing when we let AI do our thinking? When we hand children devices that fragment their attention before they can read? When we build systems that make the hard work of mastery feel optional?

The OSS knew what it was doing. It understood that the accumulation of small inefficiencies, each one seemingly reasonable in isolation, could bring an organisation to its knees.

We’re doing the same thing to the human mind. And unlike the saboteurs of 1944, we’re not even doing it on purpose.

The manual was declassified in 2008. It’s available online, free to read (here). I recommend it. Rebecca’s book offers the antidote. The saboteurs had a plan. Now, at least, we have one too.

Tech for good example of the month: Alba Health

This month’s edition has focused heavily on what technology is doing to children. It seems fitting to end with an example of what technology can do for them.

Alba Health is a gut health startup using AI and microbiome science to support childhood gut health. Designed for children aged 0 to 12, the platform offers research-grade gut analysis, personalised nutrition plans, and one-to-one coaching from certified health experts.

The science is increasingly clear: the gut microbiome in early childhood influences everything from immune function to mental health. Conditions like allergies, eczema, and asthma often have roots in gut dysbiosis that, if caught early, can be addressed through dietary and lifestyle changes rather than medication.

Founded in 2022 by molecular biologist Eleonora Cavani and microbiome expert Professor Willem M de Vos, Alba Health emerged from Cavani’s personal experience. Severe eczema that had plagued her for years resolved through gut-focused lifestyle changes. The question she asked: why isn’t this knowledge accessible to parents when it matters most?

What makes Alba Health interesting isn’t just the AI, which analyses microbiome data and generates personalised recommendations, but the human layer on top. Every family gets access to certified health coaches who translate the science into practical advice. The technology augments human expertise rather than replacing it.

This is the distinction Adam Hammond drew when discussing quantum computing: technology that serves human capability, rather than substituting for it. Alba Health uses AI to process complex microbiome data at scale, but the relationship, the trust, the behaviour change stays human.

It’s also preventive rather than reactive. Instead of waiting for chronic conditions to develop and then treating them, Alba Health aims to intervene before the damage is done. We could all learn a lot from Alba Health’s approach.

Do you know of a “tech for good” company, initiative, or innovation that deserves a spotlight? I’m building a database of examples for future editions. Drop me a line at oliver@pickup.media.

Statistics of the month

🌊 AI tsunami warning

The head of the International Monetary Fund, Kristalina Georgieva, told Davos that AI will be “a tsunami hitting the labour market”, with young people worst affected. The IMF expects 60% of jobs in advanced economies to be affected by AI – enhanced, eliminated, or transformed – and 40% globally. (IMF)

😰 Job anxiety rises

Some 27% of UK workers worry their jobs could disappear within five years due to AI. Meanwhile, 56% say their employers are already encouraging AI use at work. The gap between encouragement and reassurance is telling. (Randstad Workmonitor 2026)

⏱️ 85 seconds to midnight

The Doomsday Clock advanced to 85 seconds to midnight, the closest it has ever been to catastrophe in its 79-year history. The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists cited nuclear tensions, climate breakdown, and, for the first time, the increasing sophistication of large language models as factors. In 2017, when I wrote about it for Raconteur to mark its 70th anniversary, it stood at two and a half minutes, the closest to the apocalypse since the 1950s. Now we’re measuring in seconds. (Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists)

💔 AI as boyfriend Two-thirds of Gen Z adults use AI chatbots as a replacement for Google searches. But the social uses are growing: 32% turn to AI for relationship or life advice, 23% use chatbots “as a friend”, and one in ten use an AI chatbot “as a girlfriend or boyfriend”. (Harvard Business Review)

📸 Deepfake abuse industrialised

A Guardian investigation identified at least 150 Telegram channels offering AI-generated “nudified” photos and videos, with users in countries from the UK to Brazil, China to Nigeria. Some charge fees to create deepfake pornography of any woman from a single uploaded photo. The industrialisation of digital abuse. (The Guardian)

⚖️ The other billion

Obesity now affects over one billion people worldwide, a figure projected to double by 2035 on current trends. As we build a “stupidogenic society” that atrophies cognitive muscles, it’s worth remembering we’ve already built an obesogenic one. The pattern is familiar. (JAMA)

Thank you for reading Go Flux Yourself. Subscribe for free to receive this monthly newsletter straight to your inbox.

All feedback is welcome, via oliver@pickup.media. If you enjoyed reading, please consider sharing it via social media or email. Thank you.

And if you are interested in my writing, speaking and strategising services, you can find me on LinkedIn or email me using oliver@pickup.media.