TL;DR: June’s Go Flux Yourself includes how AI is after our weekends, why it should be renamed ‘alien intelligence’, the growing loneliness epidemic (and rising demand for AI girlfriends), and the enrichment of hanging out with old people …

Image created on Midjourney with the prompt “a young man looking lonely with only his headphones and tablet on in the style of a Henri Bonnard painting”

The future

“I want AI to do my laundry and dishes so that I can do art and writing, not for AI to do my art and writing so that I can do my laundry and dishes.”

Author Joanna Maciejewska posted this on X in late March, and it’s been repeated or paraphrased at many of the tech conferences I’ve attended, as a journalist or speaker, in June – because it’s so right.

The science-fiction writer called out the “wrong direction” of AI. I thought of her clever line when I heard historian and best-selling author (of Sapiens and other brilliant books) Yuval Noah Harari’s keynote at the Future Talent Summit in Stockholm on June 18.

He warned starkly about the potential consequences of AI adoption, particularly in the financial sector. Harari cautioned that the rise of AI could eliminate weekends and other crucial rest periods.

“In Wall Street, markets close on Friday and open again on Monday; weekends are baked into the system because financiers need rest – but now, if they rely on AI agents, they don’t,” Harari explained. “This means there is an increasing pressure to abolish rest in more and more places.”

He stressed the need to halt this trend. “We have to resist it if we want to keep our sanity and our health, but the pressure against us is immense.”

I participated in about a dozen technology and future-of-work-related events in June, and it strengthened my view that in the excitement of AI, humans are increasingly – and alarmingly – an afterthought.

It’s 22 years since then-United States defence secretary Donald Rumsfeld, responding to a question about the supply of weapons by Iraq to terrorist groups, said: “There are known knowns – things we know we know. There are known unknowns – some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns – the ones we don’t know, we don’t know.”

There are unknown unknowns with the development of AI, but there are known knowns that are not being addressed. Indeed, as Harari’s clear logic shows, as AI systems become more sophisticated, there’s a risk that humans may be expected to match their 24/7 availability, potentially eroding long-established practices of rest and recuperation. Forget about the four- or even three-day week.

Harari also argues that we should reconsider the very meaning of AI. In his view, AI doesn’t stand for “artificial intelligence”, but rather “alien Intelligence”. This shift in terminology reflects a profound insight into the nature of AI’s development. “As AI evolves, it is becoming less artificial and more alien,” he stated in the keynote. “AI is evolving an alien type of intelligence – neither human nor even organic.”

This concept of “alien intelligence” underscores a critical misunderstanding of how we evaluate AI progress. Many debates centre around when AI will reach human-level intelligence, but Harari suggests this metric is fundamentally flawed – it’s like people are, lemming-like, falling into the Turing trap (see more here on that).

“People often make the mistake of evaluating AI by the metric of human-level intelligence,” Harari said. “It’s like trying to define and evaluate aeroplanes by the metric of bird-level flight. When will aeroplanes fly like birds? Never.”

Instead of progressing towards human-like cognition, AI is developing in ways entirely foreign to human thought processes and behaviours. This alien nature is further emphasised by the incredible speed at which AI learns and changes – an utterly inhuman pace.

This reframing of AI as “alien intelligence” offers a fresh lens through which to view the rapid advancements in this field, encouraging a more nuanced and perhaps more accurate understanding of where AI technology is heading – and, most importantly, where it is likely to leave humans.

The present

“All the lonely people, where do they all come from?”

This famous line is from Eleanor Rigby, a song released by The Beatles 58 years ago, on August 5, 1966, the week after England’s men won the football World Cup. The first televised World Cup took place in Switzerland only a dozen years earlier. (As an aside, some 140 goals – at 5.38 per match – were scored as West Germany triumphed for the first time. How things have changed, hey, Gareth?)

First came television, then computers, followed by social media, and now artificial intelligence (AI) – technology excitedly marketed as enlightening, enabling, educating, empowering, and connecting us. But has it done the opposite?

There was indeed a grim coincidence that London Tech Week and Loneliness Awareness Week fell on the same seven days in mid-June. One could argue that the cutting-edge technology celebrated during the former may contribute to the social isolation addressed by the latter. And, looking to the future, it seems that we are becoming more lonely.

Gallup’s State of the Global Workplace report, released that same week, offered sobering insights. While media attention focused on record-equalling (but still miserably low) global workforce engagement (23%) and the massive economic cost of disengagement ($9 trillion annually), another troubling statistic emerged: one in five employees worldwide report feeling lonely daily.

This statistic deserves careful consideration: 20% of the workforce experiences daily loneliness – namely, a profound sense of sadness stemming from a lack of social connections or companionship. Further, Gallup’s research revealed an unsettling correlation: those who work entirely remotely, thanks to advanced technology, report the highest levels of loneliness.

The theme for Loneliness Awareness Week was “random acts of kindness”. It’s harder to fulfil that goal if you are holed away at home, with no need to commute or physically interact with anyone other than those you live with.

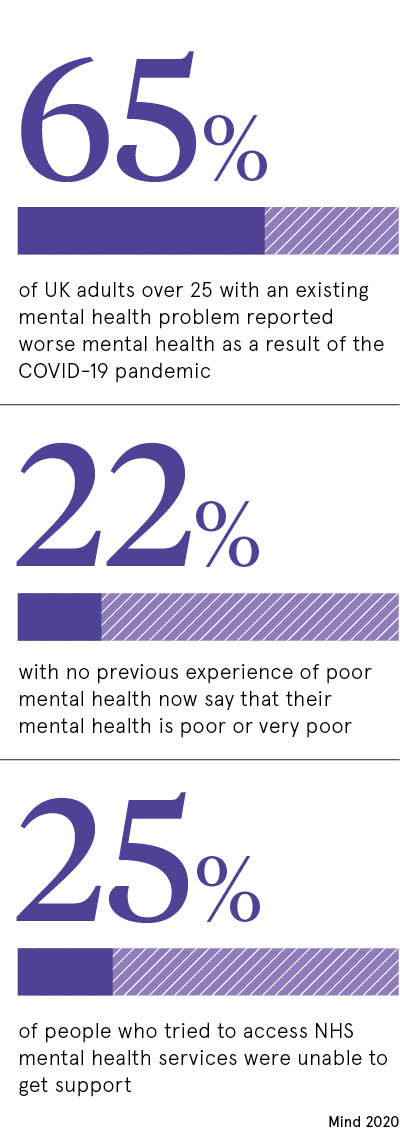

It’s worth clarifying the impact of loneliness on one’s health. Here are some statistics from Loneliness Awareness Week:

- Loneliness is as harmful as obesity or smoking 15 cigarettes a day.

- Loneliness is likely to increase your risk of death by 26%.

- Loneliness and social isolation have been linked to a 30% increase in the risk of having a stroke or coronary artery disease.

- In total, 45% of adults feel occasionally, sometimes, or often lonely in England. This equates to 25 million people.

- Disconnected communities could be costing the UK economy £32 billion every year.

While these numbers are all depressing, it’s this one that concerns me the most: 16-29-year-olds are twice as likely as those over 70 to experience loneliness.

It’s a subject close to the heart of Scott Galloway, serial entrepreneur, provocateur, and professor of marketing at New York University Stern School of Business (who, almost exactly two years ago, called me “full of sh1t). At a recent Wall Street Journal conference, Galloway said young people’s time spent out of the house is a forward-looking indicator of their success. Ironically, it sparked a reaction from hordes of the young people he was talking about on … TikTok.

At the start of this year, I heard Galloway discuss this topic, albeit briefly – as the session was titled Can AI be contained? “The biggest threat we’re not discussing enough is loneliness,” he said. “We’re raising a generation of young men who, due to fewer economic opportunities, changes in dating dynamics, and slower maturation, are retreating into AI-created relationships. They’re choosing the low-risk comfort of artificial companionship over the challenges of real human connections.”

He continued: “This trend is creating a cohort of socially unskilled young men who are disconnecting from society. Instead of facing the risks and potential rejection involved in job hunting or dating, they’re opting for faux relationships with increasingly sophisticated algorithms. While the media hypes up various AI threats, the real dangers are more subtle: AI-enhanced misinformation that improves daily, and the increasing loneliness as people choose low-reward algorithmic relationships over genuine human interactions. The true richness of life lies in real relationships, but many are opting for the easier, artificial alternative.”

It’s certainly true that AI companions are surging in popularity, with a staggering 225 million lifetime downloads on the Google Play Store alone, according to research from software company SplitMetrics published in March. However, a striking gender disparity has emerged: AI girlfriends are overwhelmingly preferred, outpacing their male counterparts by a factor of seven.

The study, which examined 38 AI chat apps offering virtual companionship and dating functions, uncovered a 49% growth in the sector since ChatGPT’s launch in November 2022. This translates to 74 million new users, predominantly men, turning to AI for romantic and social interactions.

This data paints a clear picture: young men are increasingly drawn to the allure of risk-free, always-available AI girlfriends. As the father of two young children, the eldest being a (currently FC24-obsessed) boy, I’m deeply worried about the long-term social implications of this trend.

More generally, though, I hear stories lamenting how children are not physically interacting with one another enough. For example, a teacher friend recently took a coach load of pupils on a ski trip to the French Alps. He expected the bus trip to be full of high jinx, as was the case when we were teens. But, he described the experience as “bittersweet”, because as soon as the kids were on the coach, they popped in their earbuds, switched on their tablets, and zoned out of reality. While easy for him to manage, it was depressing that no one was talking.

A lawyer mum I met at a future-of-work symposium told a similar story. Her outgoing daughter, keen to meet new people, recently went on a ski trip, only to find that in the evenings, everyone else her age wanted to stay in their rooms and look at their screens rather than bond over fondue. Talk about pisted off.

The past

Last year, Dr Vivek H. Murthy, the United States Surgeon General, issued an “advisory on the healing effects of social connection and community” in a document titled Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation.

He wrote: “If we fail to [stop the rise in loneliness], we will pay an ever-increasing price in the form of our individual and collective health and well-being. And we will continue to splinter and divide until we can no longer stand as a community or a country. Instead of coming together to take on the great challenges before us, we will further retreat to our corners – angry, sick, and alone.”

Since 2017, I have been a “befriender” for Linking Lives UK, a charity that pairs volunteers with isolated older people. It’s been incredibly rewarding. The hour or two a week I spent with Terry, my original “friend”, who would have turned 100 next year, was illuminating – I was fortunate to be provided with a unique glimpse into another time.

We were matched due to our love of jazz. We traded music stories, although his were of significantly higher value. For instance, he was in the crowd at a packed Wembley Stadium when Louis Armstrong played in a boxing ring. Terry recalled that the great American trumpeter was accompanied by a one-legged tap dancer, Peg Leg Pete.

Given Terry was born in 1925 – the same year that British explorer Percy Fawcett disappeared in the Amazon and John Logie Baird successfully transmitted the first television pictures here in the capital – we had plenty to discuss, and I had much to learn. As a technology and business journalist, it was always educational to see how people lived (happily, for the most part) without screens, bings, pings, and other distractions.

I read the eulogy at Terry’s funeral a couple of years ago, and I often think of him, and his troubles getting to grips with tech – trying to help him speak to an automated banking system, for example. He taught so much, and all he wanted in return was not to be lonely.

Me and Terry in 2018

Statistics of the month

- Some 88% of global workers are currently worried about losing their jobs (Edelman Trust Barometer 2024).

- However, 81% of office workers think AI improves their job performance (SnapLogic).

- By 2030, about 27% of current hours worked in Europe (and 30% of hours worked in the United States) could be automated, accelerated by generative AI. Further, Europe could require up to 12 million occupational transitions – double the pace observed before the COVID-19 pandemic (McKinsey).

Stay fluxed – and get in touch! Let’s get fluxed together …

Thank you for reading Go Flux Yourself. Subscribe for free to receive this monthly newsletter straight to your inbox.

All feedback is welcome, via oliver@pickup.media. If you enjoyed reading, please consider sharing it via social media or email. Thank you.

And if you are interested in my writing, speaking and strategising services, you can find me on LinkedIn or email me using oliver@pickup.media.