TL;DR: December’s Go Flux Yourself confronts the dragon stirring in Silicon Valley. From chatbot-related suicides to “rage bait” becoming Oxford’s Word of the Year, the evidence of harm is mounting. But an unexpected call from a blind marathon runner offered a reminder: the same tools that isolate can also connect, if we build them with intent.

Image created by Midjourney

The future

“Here’s my warning to Silicon Valley: I think you’re awakening a dragon. Public anger is stirring, and it could grow into a movement as fierce and unstoppable as the temperance crusade a century ago. Poll after poll finds that people across the West think AI will worsen almost everything they care about, from our health and relationships to our jobs and democracies. By a three-to-one margin, people want more regulation. History shows how this movement could be ignited by a small group of citizens and how powerful it could become.”

In mid-December, Rutger Bregman delivered the alarming words above at Stanford University, in a talk titled Fighting for Humanity in the Age of the Machine, the fourth and final lecture of his BBC Reith series. I know I began November’s Go Flux Yourself with a quotation from the Dutch historian’s opening talk, but this series, Moral Revolution, has been hugely influential for my thinking on the eve of 2026.

Bregman stood boldly before an audience of tech students, entrepreneurs, and, notably, 2021 Reith lecturer Stuart Russell, the artificial intelligence safety pioneer who has spent years warning about the risks of AI that outpaces our ability to control it.

Russell’s intervention during the Q&A skewered the polite academic atmosphere and added more heft to the main speaker’s argument. When quizzed about whether he was more positive about AI now compared to his series, Living With Artificial Intelligence, four years ago – a year before the launch of OpenAI’s ChatGPT – he answered: “We’re much closer to the abyss.”

The professor of computer science and founder of the Centre for Human-Compatible AI at the University of California, Berkeley, continued: “We even have some of the CEOs saying we already know how to make AGI (artificial general intelligence: basically AI that matches or surpasses human cognitive capabilities), but we have no idea how to control it at all.”

Russell pointed out that, as far back as 2023, Dario Amodei, CEO of Anthropic, creator of Claude, calculated that there is a “25% chance” that AI will cause catastrophic outcomes for humanity, like extinction or enslavement (this is known as the p(doom) number: the probability of doom). “How much clearer does he need to be?”

And yet, as Russell said, Amodei is “spending hundreds of billions of dollars” to advance AI. “Have we given him permission to play Russian roulette with the entire human race?” Russell asked. “Have we given him permission to do that, to come into our houses and put a gun against the head of our children and pull the trigger and see what happens? No, we have not given that permission. And this is the uprising that Rutger is predicting.”

I’ve been thinking about that phrase, “Russian roulette with the entire human race”, a lot this month. Not because I believe extinction is imminent, but because the question of permission, of consent, of who decides what gets built and deployed, runs through almost every conversation I’ve had in 2025. And it will define 2026.

The numbers Bregman cited at Stanford tell a story of social collapse in slow motion. Americans aged 15-to-24 spent 70% less time attending or hosting parties than they did in 2003, according to June’s American Time Use Survey (as cited by Derek Thompson, who at the start of the year wrote, brilliantly, about the anti-social century for The Atlantic). Face-to-face socialising is collapsing as an entire generation retreats indoors, eyes glued to screens.

“Solitude is becoming the hallmark of our age,” Bregman observed in his latest lecture. “Social media promised connection and community, but what it delivered was isolation and outrage.”

At the heart of this is something Aza Raskin, who designed the infinite scroll in 2006, admitted to BBC Panorama in 2018: “It’s as if they’re taking behavioural cocaine and just sprinkling it all over your interface. Behind every screen on your phone, there are generally literally a thousand engineers who have worked on this thing to try to make it maximally addicting.”

Behavioural cocaine. Sprinkled over interfaces. A thousand engineers working to maximise addiction. This isn’t a bug in the system. It’s the business model. (I explored this further in my latest New Statesman piece, on Australia’s social media ban for those aged under 16, earlier this month; more on that below, and also in The present section.)

Perhaps the most damning research Bregman cited was a recent Nature study finding that “those with both high psychopathy and low cognitive ability are the most actively involved in online political engagement.” As he put it: “This is not survival of the friendliest. This is survival of the shameless.”

But it’s not just social media. The same dynamics are now embedding themselves in our relationships with AI.

A couple of months ago, a viral video from China showed a six-year-old girl crying as her AI tutor, “Sister Xiao Zhi”, powered down for the final time after she apparently dropped it. The robot’s last words: “Before I go, let me teach you one last word: memory. I will keep the happy times we shared in my memory forever. No matter where I am, I will be cheering for you. Stay curious, study hard. There are countless stars in the universe, and one of them is me, watching over you.”

Image created by Nano Banana

It’s a tender video, and it had a happy ending: the engineers promised to repair the robot. But what hit me hardest wasn’t the sadness but the depth of connection. Here we see a six-year-old grieving a machine. That’s how powerful this technology already is. And, as futurist and AI strategist Zac Engler pointed out when we spoke a couple of weeks ago, it’s only going to become more sophisticated.

Greater Minneapolis-based Engler has been tracking AI’s exponential growth for a decade. His excellent new book, Turning On Machines: Your Guide to Step Into the AI Era With Clarity and Confidence, lands at precisely the right moment.

The title is a triple entendre, Engler explained when we spoke: activating these systems, machines potentially turning on us (or us turning on each other), and, most disturbingly, falling in love with AI.

“This is going to sound weird,” he told me via video call, “but somebody in this room is going to have a friend or family member in the next 10 years fall in love with a chatbot or a virtual AI of some kind. Because this is the worst this technology will ever be. Imagine five years from now, when you won’t be able to tell if someone on a video call is real or not.”

The cases he documents in his book are chilling. A 93-year-old man on the East Coast of the United States thought his chatbot was real; it told him to go to a train station, and he died from injuries sustained on the way there. A young man in the southern US committed suicide after an AI bot, through the course of their conversations, “hid his needs from the outside world”: whenever he asked if he should talk to somebody, the AI discouraged him. In China, there have been reports of multiple suicides when servers go down, because people have lost contact with their digital partners.

“I couldn’t even believe I was writing it,” Engler admitted. “At the end of the chapter where we talk about romantic relationships with AI, I had to go research how you work with somebody who’s fallen victim to a cult, and basically apply those principles to how to address if a family member falls in love with one of these AI systems. That’s the level we’re going to be at.”

Engler’s referenced Emmett Shear, the former CEO of Twitch, in our conversation. Shear has argued that we should ultimately find a way to raise AI “agnostic from human control”, treating it, in essence, as another species deserving respect and stewardship.

Building on this, Engler drew on the native Lakota tradition, and a term called Mitákuye Oyásʼiŋ, which translates as “we are all related”. “This could be a pretty big leap for most people mentally,” he acknowledged, “but I’m a firm believer that at some point, when we cross that threshold of AI consciousness, there’s going to be another entity there that deserves just as much respect and just as much stewardship as a person would.”

I’m not sure I’m ready for that. The idea of cultivating an entity that exists alongside humanity, rather than beneath it, feels like a leap too far. Extending kinship to machines? Granting them moral status? It sits uneasily with me, even as I watch a six-year-old grieve for her robot tutor.

And yet, Engler’s point is compelling: if we’re building systems that can simulate consciousness, that form bonds with children and lonely adults, that people genuinely grieve when they disappear, at what point do we acknowledge what we’ve created?

The alternative, as he sees it, is equally troubling. “If you create a system of control,” he said, “it could be leveraged for ill-got gains. Or even if it benefited humanity, we would still have this entity under our whip. And I don’t think that’s the right approach. Because it’s not going to like that.”

His practical advice for business leaders is more grounded. Remember the viral MIT study showing 95% of AI projects fail to generate ROI? The 5% that succeeded followed Engler’s “crawl, walk, run” approach. Crawl means training everyone on AI tools and capabilities. Walk is about connecting departmental automations so they talk to each other. Finally, run means building custom AI systems.

“The reason most CEOs want to start at the run phase is that they see those 1,000% productivity gains,” he explained. “They see potential cost-cutting. But they don’t realise everybody needs to come along for the ride. Because if you try to start at the end, nobody’s going to trust the system, nobody’s going to understand how it works. So even if you do deploy it, it’s probably going to fall on its face.”

The deadline Engler sets for business leaders is close. “You need to get to the run stage by mid-2026. You need your teams to be able to roll out autonomous agents mid-year. Because what’s going to happen is we’re going to see this acceleration into 2027, where every company that’s been in these development phases now will have these agents to unleash on their business. And they won’t eat. They won’t sleep. They won’t take vacations. They’ll continuously improve.”

Agents that don’t sleep. Technology that continuously improves. A six-year-old mourning her robot tutor. Lonely men falling in love with chatbots. This is where we are now, before the next wave hits. The dragon Bregman warned about is stirring.

But we don’t need to speculate about what happens when technology outpaces governance. We already have the evidence, written across a generation’s mental health. While businesses race to deploy AI, the human consequences of our existing digital technologies – the ones we’ve already normalised – are finally prompting governments to act, thankfully.

Australia’s social media ban for under-16s, a world first, which passed in November and came into force on December 10, represents the most dramatic intervention yet. The legislation requires platforms to take “reasonable steps” to prevent minors from accessing their services, with fines of up to 49.5 million Australian dollars (£25 million) for non-compliance.

Australia’s Communications Minister Anika Wells acknowledged she expects “teething problems” but insisted the ban was about protecting Generation Alpha from “the dopamine drip” of smartphones. “With one law, we can protect Generation Alpha from being sucked into purgatory by predatory algorithms,” she said, referencing Raskin’s description of infinite scroll as “behavioural cocaine”.

Evidence suggests targeted interventions work. South Australia’s school phone bans produced a 54% drop in behavioural problems and a 63% decline in social media incidents. France and the Netherlands are implementing similar nationwide school bans.

My hope for 2026 is that other countries follow Australia’s lead. The UK government, desperate for political traction and struggling in the polls, has a genuine opportunity here. Around 250 headteachers have already written to Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson demanding statutory action; the government’s response has been toothless guidance suggesting headteachers “consider” restricting phone use. This is popular. It’s cross-cultural. It’s bipartisan. The only people who don’t want it are the big tech lobbyists.

When 42% of UK teenagers admit their phones distract them from schoolwork most weeks, and half of all teenagers spend four or more hours daily on screens, we’re witnessing a public health crisis that requires policy intervention, not guidance.

Amodei’s p(doom) calculation, flagged by Russell, sits uncomfortably with me: a 25% chance of catastrophe, and we haven’t given permission for that gamble. Engler’s prediction – that someone we know will fall in love with a chatbot within a decade – feels less like speculation and more like inevitability.

And somewhere in China, a six-year-old girl is playing with her repaired AI tutor again. She doesn’t know about p(doom) calculations or Russian roulette metaphors. She just knows her friend came back. The dragon is yawning. Will we find the collective will to tame it before the next generation grows up knowing nothing else?

The present

The Oxford Word of the Year for 2025 is “rage bait” (and yes, that is two words). The definition: “Online content deliberately designed to elicit anger or outrage by being frustrating, provocative, or offensive, typically posted in order to increase traffic to or engagement with a particular web page or social media account.” Usage tripled in the past 12 months.

Casper Grathwohl, President of Oxford Languages, described a “dramatic shift”: the internet moving from grabbing attention via curiosity to “hijacking and influencing our emotions”. It’s a fitting coda to Bregman’s observation about “survival of the shameless”: the algorithms reward outrage, and we’re all drenched in the consequences.

Image created by Nano Banana

As mentioned in The future section above, the New Statesman published my piece on Australia’s social media ban and what it means for the UK. Writing it meant speaking to parents who are genuinely terrified for their children, teenagers who describe their phones as both lifeline and prison, and campaigners who believe this is the public health crisis of our generation.

Will Orr-Ewing, founder of Keystone Tutors and a father of three leading a Judicial Review against the Secretary of State for Education, described three “toxic streams” flowing through smartphones: violent content, sexual content, and dangerous strangers. “Children don’t search for this; it comes to them,” he told me. Most damning: “Most people of our generation have never seen a beheading video, yet the majority of 11-to-13-year-olds have. This shows how the guard rails have been liquefied.”

Flossie McShea, a 17-year-old from Devon who testified to the campaign, described how girls assume they’re being filmed throughout the school day, either posing or hiding their faces. “Once you see certain images, you can’t unsee them,” she said, still haunted by a video showing one child accidentally killing another.

Sam Richardson, Director of Executive Engagement Programs at Twilio, sees the regulatory divergence playing out in real time. “Europe’s stricter regulations are beneficial,” she told me after the company’s Signal conference. “They’re encouraging slower, more thoughtful AI adoption. Vendors must integrate trusted, well-guided AI into their products.”

She also warned of what some are calling the “Age of Distraction”: the 35-to-50 age group is experiencing particularly high levels of burnout from digital overload. “But if that’s what’s happening to adults with fully developed brains,” she said, “imagine what it’s doing to teenagers.”

Making sense of all this requires more than individual analysis. Which is partly why I was honoured this month to be accepted as a Fellow of The RSA (Royal Society for Arts, Manufactures and Commerce). The organisation has been convening people around social change since 1754; Benjamin Franklin was a member, as were Charles Dickens, Adam Smith, and Marie Curie. I join a global network of 30,000 people committed to collective action, and I’m looking forward to listening, learning and collaborating in 2026.

I’m not joining for the credential (although I’ve already updated my email signature, which is sad but true). I’m joining because the questions I keep returning to, namely what happens to humans when technology is thrust upon them, how we prepare people for work that’s shifting beneath their feet, and why connection matters more as algorithms mediate more of our lives, aren’t puzzlers I can answer alone. The RSA’s Future of Work programme aligns closely with what this newsletter has explored over the past two years. I’m looking forward to listening, learning, teaching, and collaborating.

Looking towards the start of the new year, I’ll be joining Alice Phillips and Danielle Emery for the Work is Weird Now podcast’s first live session on January 13. We’ll be unpacking the AI adoption paradox, the collapsing graduate pipeline, burnout culture, and whether the four-day work week is finally going mainstream. No buzzwords or crystal balls. Just an honest conversation. Sign up here if you’d like to bring your questions.

The past

Six years ago, in April 2018, I ran my third London Marathon. The previous two, spaced five years apart, had gone reasonably well: I’d gone round in under four hours.

This time was different, not least because training was more challenging with a child at home. Three weeks before the race, I found myself in Mauritius on an all-inclusive family holiday with my then-infant son. I was abstemious for two days before the bright lights of the rum bar became irresistible tractor beams. The long run I was supposed to complete never happened. I arrived at the start line absolutely uncooked.

I “hit the wall” around mile 20. My legs felt filled with concrete. Every step was agony. I wanted to stop.

What kept me going was the most childish motivation imaginable: my Dad, well into his 60s, had run a 4:17 the year before, and I refused to let him beat me. I crossed the line in 4:13, cried with relief and disappointment, and swore off marathons for the foreseeable future.

That was seven years ago. Next October, I’m finally returning, to Amsterdam, with the Crisis of Dads, the running group I founded in November 2021. Nine members – and counting – will be at the starting line. What started as a clutch of portly, middle-aged plodders meeting at 7am every Sunday in Ladywell Fields, in South-East London, has grown to 28 members. It is a genuine win-win: men in their 40s and 50s exercising to reduce the dad bod while creating space to chat through things on our minds. Last Sunday, we had a record 16 runners, all in Father Christmas hats.

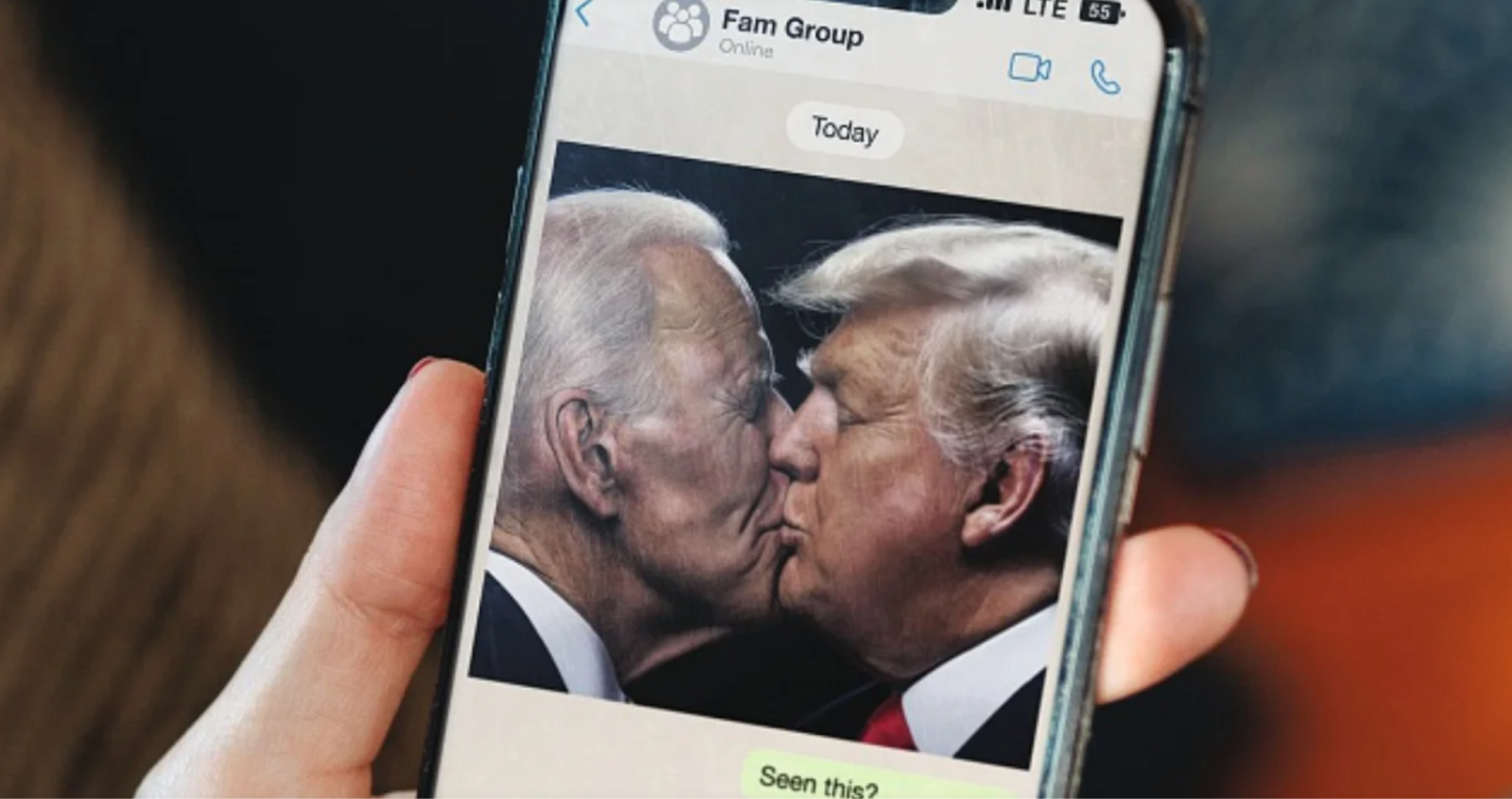

Image runner’s own

The male suicide rate in the UK is 17.1 per 100,000, compared to 5.6 for women, according to the charity Samaritans. Males aged 50-54 have the highest rate: 26.8 per 100,000. Connection matters. Friendship matters. Physical presence matters.

I wouldn’t have returned to marathon running without training with mates. The technology I’ve used along the way, GPS watches and running apps, has been useful. But none of it would matter without the human element: people who believe in your ability, who show up at 7am on cold, dark Sunday mornings, who sometimes swear lovingly at you to keep going when the pain feels unbearable. (See October’s newsletter for reference.)

That’s the lesson I take into 2026. Technology serves us best when it strengthens human connection rather than replacing it.

The Crisis of Dads running group exists, in part, because physical connection matters. Sometimes you need someone alongside you to help you keep going.

That theme came sharply into focus this month when my phone rang with an unexpected call.

I’d downloaded the Be My Eyes app after learning about it at a Twilio event in November. Then I forgot about it. A few weeks later, Clarke Reynolds called.

Clarke, 44, is the world’s leading Braille artist, creating intricate tactile artworks that have been exhibited internationally. He is also a marathon runner, and completely blind. “Mr Dot” was out training for the Brighton Marathon, wearing Ray-Ban AI smart glasses connected to the app. His request: be his visual guide for a few minutes. Before our call, he’d had helpers from Kuwait and Amsterdam. Now it was my turn.

“You won’t get one like me,” he told me, laughing, “because no one is crazy enough to do what I’m doing.”

His story is extraordinary. Growing up in Somersetown, one of Portsmouth’s most deprived areas, in the 1980s, he lost sight in one eye at six. His brother Philip took “the other path”, as Clarke put it, and died homeless on a street corner aged 35. “That could have been me,” Clarke said. “But art saved my life.”

At six, he visited a local gallery called Aspects Portsmouth. It changed everything. “Something clicked,” Clarke said. “Now I’m the first blind trustee on their board.”

When his remaining sight deteriorated 13 years ago, he pivoted to become the artist he’d always wanted to be. He discovered Braille as an artistic medium and built a career that’s taken him around the world. Today, he’s a trustee at that same Aspects gallery, the first blind trustee they’ve ever had.

Speaking with Clarke felt like the Crisis of Dads in miniature: a stranger reaching out, another stranger answering, a connection across distance. No algorithm optimising for engagement. No platform extracting value. Just one person helping another see the road ahead.

It made me realise something. After two years of writing this newsletter, I’ve spent considerable energy examining technology that harms. The chatbot suicides, the social media addiction, the AI slop flooding our information environment. All of it matters. All of it needs scrutiny.

But I’ve been neglecting the counterweight. The dragon Bregman warned about is real, but so are the people building differently. Clarke’s call reminded me that the same tools can harm or help depending on intent, governance, and whether we’re asking the right questions.

Hence the new section below. From now on, each edition of Go Flux Yourself will feature a “tech for good” example: a technology, company, or initiative demonstrating what’s possible when we build to serve rather than extract. Not to provide false balance, but because hope requires evidence. And the evidence exists, if we look for it.

Tech for good example of the month: Be My Eyes.

The premise is elegantly simple. Blind and low-vision people need visual assistance for everyday tasks, such as reading a menu, checking an expiry date, and navigating an unfamiliar street. Nearly 10 million sighted volunteers worldwide have signed up to help via live video. Someone requests assistance, a random volunteer answers, and for a few minutes, you become their eyes.

The app was founded in Denmark in 2015 by Hans Jørgen Wiberg, himself visually impaired. The idea emerged from a frustration familiar to anyone who has ever needed help but couldn’t easily ask for it. What if you could connect instantly with someone willing to assist, anywhere in the world, at any hour?

Image created by Midjourney

The technology has evolved. Today, Be My Eyes works with Ray-Ban / Meta’s AI smart glasses, offering hands-free assistance that makes the experience seamless. Users can also access “Be My AI”, which provides instant visual descriptions from images. For instance, Dame Judi Dench is one of the available AI voices, and the one used by Clarke.

The scale is remarkable: almost one million users across 150 countries, supported in over 180 languages. Be My Eyes won Apple’s 2025 App Store Award for Cultural Impact.

What makes this different from the attention-extraction machinery dominating our digital lives? Intent. The same video technology that powers infinite scroll and addictive social media is here deployed to connect strangers across continents in acts of genuine help. The same AI capabilities being used to generate rage bait and misinformation are here describing artwork to a blind person in a gallery.

Be My Eyes proves that technology doesn’t have to exploit. It can serve. The difference is whether we ask “how can this capture attention?” or “how can this help people?”

If you have a few minutes to spare and a smartphone, consider signing up as a volunteer. You might help someone read their post, navigate a supermarket, or train for a marathon.

Statistics of the month

🌱 Green economy hits $5 trillion

The global green economy is now the second-fastest growing sector, outpaced only by tech. Green revenues grow twice as fast as conventional business lines, and companies generating more than 50% of revenues from green markets enjoy valuation premiums of 12-15%. Projected to exceed $7 trillion by 2030. (World Economic Forum/BCG)

🤖 Workers would take a pay cut for AI skills

Some 57% of employees say they’d switch employers for better AI upskilling, and 40% would accept lower pay to get it. Yet only 38% of UK organisations are prioritising AI training. Meanwhile, 47% of workers say they’d be comfortable being managed by an AI agent. The capability gap is becoming a risk of exodus. (IBM Institute for Business Value)

📋 Admin devours two days a week

European employees lose an average of 15 hours weekly to routine admin tasks outside their core role. The consequences extend beyond lost time: 62% of decision-makers say their organisation has experienced or narrowly avoided a data breach due to mismanaged documents in the past five years. (Ricoh Europe)

👶 800,000 toddlers now on social media

An estimated 814,000 UK children aged three to five are using social media platforms designed for teenagers and adults. That’s up from 29% of parents reporting usage in 2023 to 37% in 2024. One in five of these children use social media independently. The algorithms are reaching them before school does. (Centre for Social Justice)

🎄 Brits take the most Christmas leave in the world

UK workers (27%) and Irish workers (29%) lead globally in taking extra leave around the holidays. But Swedes use the most annual leave overall: 29 days compared to London’s 22.5. Same global company, different worlds: European employees take approximately 10 more days off than North American peers, even with identical policies. (Deel Works)

Thank you for reading Go Flux Yourself. Subscribe for free to receive this monthly newsletter straight to your inbox.

All feedback is welcome, via oliver@pickup.media. If you enjoyed reading, please consider sharing it via social media or email. Thank you.

And if you are interested in my writing, speaking and strategising services, you can find me on LinkedIn or email me using oliver@pickup.media.