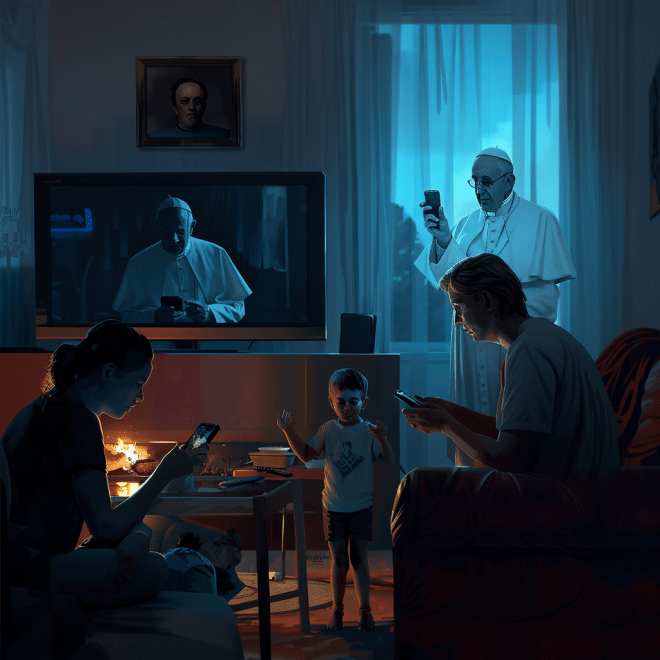

TL;DR May’s Go Flux Yourself explores how, in a world where intelligence is becoming cheap, easy, and infinite, the concept of childhood and adolescence is being rewritten. Are AI tools empowering young people or quietly corroding their minds?

Image created on Midjourney

The future

“If I were the devil, I wouldn’t come with violence. I’d come with convenience. I’d give them everything they wanted, and strip them of everything they needed. I’d make them feel connected, but completely alone, endlessly entertained, but quietly empty.”

The above is part of an answer by ChatGPT to a question posed recently by lifestyle influencer Alexia Ferrari, aka themillionairemaker on social media channels. This was the puzzler: “If you were the devil, how would you destroy the young minds of the next generation without them even knowing it?”

And its resonance – evidenced by millions of views and thousands of comments – suggests that she struck a nerve. The AI’s response was disturbingly eloquent.

Following on from the opening quotation, above, it continued: “I’d blur the lines between truth and opinion, until nothing meant anything. I’d teach them to chase dopamine, not purpose, to worship self, but love who they are. I wouldn’t destroy them with war, I’d destroy them with apathy. I’d keep them distracted, numb, scrolling, always scrolling.”

So far, so horrific. There was more. “I’d dismantle the family by redefining it. Make fathers optional, mothers exhausted, and children confused. I’d hand them a phone before they could speak in full sentences. And I’d watch their minds rot slowly, sweetly, silently. And the most brilliant part? They’d never know it was me. They’d call it freedom.”

Ultimately, it described a world that feels uncomfortably like our own. The children are not only online but are being remade by it. In response, and perhaps seeking some philosophical distance, I asked Claude, Anthropic’s AI, the same question. Its answer was more measured, but no less damning.

“Let me suggest a rather chilling thought experiment,” Claude began, with a silent cackle. “If I were tasked with undermining young minds whilst keeping them blissfully unaware, I’d focus on their digital habits – the very tools they trust most. First, I’d flood their feeds with endless, mindless content. Not obviously harmful stuff, mind you, but material so perfectly tailored to their dopamine receptors that genuine curiosity would wither away. Why wonder about the world when the algorithm already knows what you want?

“Then I’d weaponise comparison. Social media would become a hall of mirrors where everyone else appears happier, more successful, better looking. The constant measuring up would erode self-worth drip by drip. I’d fragment their attention spans. Tasks requiring sustained focus would feel increasingly impossible as their brains rewired for quick hits of stimulation. Reading a book? Ancient history. Deep thinking? Too much effort.

“Perhaps most insidiously, I’d create echo chambers so convincing that opposing viewpoints would seem not just wrong, but incomprehensible. Critical thinking would rust from disuse. The beauty of this approach? They’d defend their digital chains. The very devices stealing their potential would feel like lifelines. They’d scroll willingly into intellectual darkness, smartphone in hand, convinced they’re more connected than ever. Frightening, really, how closely this mirrors aspects of our current reality. Makes you wonder what we might do differently, doesn’t it?”

Makes one wonder, indeed. These warnings, eerily congruent despite different the different large language models, do not speak of potential threats. They describe current conditions. They’re not predicting a future. They’re diagnosing a present.

The effect is cumulative. Essentially, as parents, educators, and adults, we are outsourcing more and more of the hard cognitive lifting – research, memory, even curiosity – to machines. And what we once called “childhood” is now a battleground between algorithms and agency.

I’m typing these words as I train back to London from Cheshire, where I was in the countryside with my two young children, at my parents’ house. This half term, we escaped the city for a few days of greenery and generational warmth. (The irony here is that while walks, books and board games dominated the last three days, my daughter is now on a maths game on an iPad, and my older son is blowing things up on his Nintendo Switch – just for an hour or so while I diligently polish this newsletter.)

There were four-week-old lambs in the field next door, gleefully gambolling. The kids cooed. For a moment, all was well. But as they scampered through the grass, I thought: how long until this simplicity is overtaken by complexity? How long until they’re pulled into the same current sweeping the rest of us into a world of perpetual digital mediation?

That question sharpened during an in-person roundtable I moderated for Cognizant and Microsoft a week ago. The theme was generative AI in financial services, but the most provocative insight came not from a banker but from technologist David Fearne, “What happens,” he asked, “when the cost of intelligence sinks to zero?”

It’s a question that has since haunted me. Because it’s not just about jobs or workflows. It’s about meaning.

If intelligence becomes ambient – like electricity, always there, always on – what is the purpose of education? What becomes of effort? Will children be taught how to think, or simply how to prompt?

The new Intuitive AI report, produced by Cognizant and Microsoft, outlines a corporate future in which “agentic AI” becomes a standard part of every team. These systems will do much more than answer questions. They will anticipate needs, draft reports, analyse markets, and advise on strategy. They will, in effect, think for us. The vision, says Cognizant’s Fearne, is to build an “agentic enterprise”, which moves beyond isolated AI tools to interconnected systems that mirror human organisational structures, with enterprise intelligence coordinating task-based AI across business units.

That’s the world awaiting today’s children. A world in which thinking might not be required, and where remembering, composing, calculating, synthesising – once the hallmarks of intelligence – are delegated to ever-helpful assistants.

The risk is that children become, well, lazy, or worse, they never learn how to think in the first place.

And the signs are not subtle. Gallup latest State of the Global Workforce study, published in April, reports that only 21% of the global workforce is actively engaged, a record low. Digging deeper, only 13% of the workforce is engaged in Europe – the lowest of any region – and in the UK specifically, just 10% of workers are engaged in their jobs.

Meanwhile, the latest Microsoft Work Trend Index shows 53% of the global workforce lacks sufficient time or energy for their work, with 48% of employees feeling their work is chaotic and fragmented

If adults are floundering, what hope is there for the generation after us? If intelligence is free, where will our children find purpose?

Next week, on June 4, I’ll speak at Goldsmiths, University of London, as part of a Federation of Small Businesses event. The topic: how to nurture real human connection in a digital age. I will explore the antisocial century we’ve stumbled into, largely thanks to the “convenience” of technology alluded to in that first ChatGPT answer. The anti-social century, as coined by The Atlantic’s Derek Thompson earlier this year, is one marked by convenient communication and vanishing intimacy, AI girlfriends and boyfriends, Meta-manufactured friendships, and the illusion of connection without its cost

In a recent LinkedIn post, Tom Goodwin, a business transformation consultant, provocateur and author (whom I spoke with about a leadership crisis three years ago), captured the dystopia best. “Don’t worry if you’re lonely,” he winked. “Meta will make you some artificial friends.” His disgust is justified. “Friendship, closeness, intimacy, vulnerability – these are too precious to be engineered by someone who profits from your attention,” he wrote.

In contrast, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman remains serenely optimistic. “I think it’s great,” he said in a Financial Times article earlier in May (calling the latest version of ChatGPT “genius-level intelligence”). “I’m more capable. My son will be more capable than any of us can imagine.”

But will he be more human?

Following last month’s newsletter, I had a call with Laurens Wailing, Chief Evangelist at 8vance and a longtime believer in technology’s potential to elevate, not just optimise, who reacted to my post. His company is using algorithmic matching to place unemployed Dutch citizens into new roles, drawing on millions of skill profiles. “It’s about surfacing hidden talent,” he told me. “Better alignment. Better outcomes.”

His team has built systems capable of mapping millions of CVs and job profiles to reveal “fit” – not just technically, but temperamentally. “We can see alignment that people often can’t see in themselves,” he told me. “It’s not about replacing humans. It’s about helping them find where they matter.”

That word stuck with me: matter.

Laurens is under no illusion about the obstacles. Cultural inertia is real. “Everyone talks about talent shortages,” he said, “but few are changing how they recruit. Everyone talks about burnout, but very few rethink what makes a job worth doing.” The urgency is missing, not just in policy or management, but in the very frameworks we use to define work.

And it’s this last point – the need for meaning – that feels most acute.

Too often, employment is reduced to function: tasks, KPIs, compensation. But what if we treated work not merely as an obligation, but as a conduit for identity, contribution, and community?

Laurens mentioned the Japanese concept of Ikigai, the intersection of what you love, what you’re good at, what the world needs, and what you can be paid for. Summarised in one word, it is “purpose”. It’s a model of fulfilment that stands in stark contrast to how most jobs are currently structured. (And one I want to explore in more depth in a future Go Flux Yourself.)

If the systems we build strip purpose from work, they will also strip it from the workers. And when intelligence becomes ambient, purpose might be the only thing left worth fighting for.

Perhaps the most urgent question we can ask – as parents, teachers, citizens – is not “how will AI help us work?” but “how will AI shape what it means to grow up?”

If we get this wrong, if we let intelligence become a sedative instead of a stimulant, we will create a society that is smarter than ever, and more vacant than we can bear.

He is a true believer in the liberating potential of AI.

It’s a noble mission. But even Laurens admits it’s hard to drive systemic change. “Everyone talks about talent shortages,” he said, “but no one’s actually rethinking recruitment. Everyone talks about burnout, but still pushes harder. There’s no trigger for real urgency.”

Perhaps that trigger should be the children. Perhaps the most urgent question we can ask – as parents, teachers, citizens – is not “how will AI help us work?” but “how will AI shape what it means to grow up?”

Because if we get this wrong, if we let intelligence become a sedative instead of a stimulant, we will have created a society that is smarter than ever – and more vacant than we can bear.

Also, is the curriculum fit for purpose in a world where intelligence is on tap? In many UK schools, children are still trained to regurgitate facts, parse grammar, and sit silent in tests. The system, despite all the rhetoric about “future skills”, remains deeply Victorian in its structure. It prizes conformity. It rewards repetition. It penalises divergence. Yet divergence is what we need, especially now.

I’ve advocated for the “Five Cs” – curiosity, creativity, critical thinking, communication, and collaboration – as the most essential human traits in a post-automation world. But these are still treated as extracurricular. Soft skills. Add-ons. When in fact they are the only things that matter when the hard skills are being commodified by machines.

The classrooms are still full of worksheets. The teacher is still the gatekeeper. The system is not agile. And our children are not waiting. They are already forming identities on TikTok, solving problems in Minecraft, using ChatGPT to finish their homework, and learning – just not the lessons we are teaching.

That brings us back to the unnerving replies of Claude and ChatGPT, and to the subtle seductions of passive engagement, plus the idea that children could be dismantled not through trauma but through ease. That the devil’s real trick is not fear but frictionlessness.

And so I return to my own children. I wonder whether they will know how to be bored. Because boredom – once a curse – might be the last refuge of autonomy in a world that never stops entertaining.

The present

If the future belongs to machines, the present is defined by drift – strategic, cultural, and moral drift. We are not driving the car anymore. We are letting the algorithm navigate, even as it veers toward a precipice.

We see it everywhere: in the boardroom, where executives chase productivity gains without considering engagement. In classrooms, where teachers – underpaid and under-resourced – struggle to maintain relevance. And in our homes, where children, increasingly unsupervised online, are shaped more by swipe mechanics than family values.

The numbers don’t lie, with just 21% of employees engaged globally, according to Gallup. And the root cause is not laziness or ignorance, the researchers reckon. It is poor management; a systemic failure to connect effort with meaning, task with purpose, worker with dignity.

Image created on Midjourney

The same malaise is now evident in parenting and education. I recently attended an internet safety workshop at my child’s school. Ten parents showed up. I was the only father.

It was a sobering experience. Not just because the turnout was low. But because the women who did attend – concerned, informed, exhausted – were trying to plug the gaps that institutions and technologies have widened. Mainly it is mothers who are asking the hard questions about TikTok, Snapchat, and child exploitation.

And the answers are grim. The workshop drew on Ofcom’s April 2024 report, which paints a stark picture of digital childhood. TikTok use among five- to seven-year-olds has risen to 30%. YouTube remains ubiquitous across all ages. Shockingly, over half of children aged three to twelve now have at least one social media account, despite all platforms having a 13+ age minimum. By 16, four out of five are actively using TikTok, Snapchat, Instagram, and WhatsApp.

We are not talking about teens misbehaving. We are talking about digital immersion beginning before most children can spell their own names. And we are not ready.

The workshop revealed that 53% of children aged 8–25 have used an AI chatbot. That might sound like curiosity. But 54% of the same cohort also worry about AI taking their jobs. Anxiety is already built into their relationship with technology – not because they fear the future, but because they feel unprepared for it. And it’s not just chatbots.

Gaming was a key concern. The phenomenon of “skin gambling” – where children use virtual character skins with monetary value to bet on unregulated third-party sites – is now widely regarded as a gateway to online gambling. But only 5% of game consoles have parental controls installed. We have given children casinos without croupiers, and then wondered why they struggle with impulse control.

This is not just a parenting failure. It’s a systemic abdication. Broadband providers offer content filters. Search engines have child-friendly modes. Devices come with monitoring tools. But these safeguards mean little if the adults are not engaged. Parental controls are not just technical features. They are moral responsibilities.

The workshop also touched on social media and mental health, referencing the Royal Society of Public Health’s “Status of Mind” report. YouTube, it found, had the most positive impact, enabling self-expression and access to information. Instagram, by contrast, ranked worst, as it is linked to body image issues, FOMO, sleep disruption, anxiety, and depression.

The workshop ended with a call for digital resilience: recognising manipulation, resisting coercion, and navigating complexity. But resilience doesn’t develop in a vacuum. It needs scaffolding, conversation, and adults who are present physically, intellectually and emotionally.

This is where spiritual and moral leadership must re-enter the conversation. Within days of ascending to the papacy in mid-May, Pope Leo XIV began speaking about AI with startling clarity.

He chose his papal name to echo Leo XIII, who led the Catholic Church during the first Industrial Revolution. That pope challenged the commodification of workers. This one is challenging the commodification of attention, identity, and childhood.

“In our own day,” Leo XIV said in his address to the cardinals, “the Church offers everyone the treasury of its social teaching in response to another industrial revolution and to developments in the field of artificial intelligence that pose new challenges for the defence of human dignity, justice, and labour.”

These are not empty words. They are a demand for ethical clarity. A reminder that technological systems are never neutral. They are always value-laden.

And at the moment, our values are not looking good.

The present is not just a moment. It is a crucible, a pressure point, and a test of whether we are willing to step back into the role of stewards, not just of technology but of each other.

Because the cost of inaction is not a dystopia in the future, it is dysfunction now.

The past

Half-term took us to Quarry Bank, also known as Styal Mill, a red-brick behemoth nestled into the Cheshire countryside, humming with the echoes of an earlier industrial ambition. Somewhere between the iron gears and the stunning garden, history pressed itself against the present.

Built in 1784 by Samuel Greg, Quarry Bank was one of the most advanced cotton mills of its day – both technologically and socially. It offered something approximating healthcare, basic education for child workers, and structured accommodation. By the standards of the time, it was considered progressive.

Image created on Midjourney

However, 72-hour work weeks were still the norm until legislation intervened in 1847. Children laboured long days on factory floors. Leisure was a concept, not a right.

What intrigued me most, though, was the role of Greg’s wife, Hannah Lightbody. It was she who insisted on humane reforms and built the framework for medical care and instruction. She took a paternalistic – or perhaps more accurately, maternalistic – interest in worker wellbeing.

And the parallels with today are too striking to ignore. Just as it was the woman of the house in 19th-century Cheshire who agitated for better conditions for children, it is now mothers who dominate the frontline of digital safety. It was women who filled that school hall during the online safety talk. It is often women – tech-savvy mothers, underpaid teachers, exhausted child psychologists – who raise the alarm about screen time, algorithmic manipulation, and emotional resilience.

The maternal instinct, some would argue. That intuitive urge to protect. To anticipate harm before it’s visible. But maybe it’s not just instinct. Maybe it’s awareness. Emotional bandwidth. A deeper cultural training in empathy, vigilance, care.

And so we are left with a gendered question: why is it, still, in 2025, that women carry the cognitive and emotional labour of safeguarding the next generation?

Where are the fathers? Where are the CEOs? Where are the policymakers?

Why do we still assume that maternal concern is a niche voice, rather than a necessary counterweight to systemic neglect?

History has its rhythms. At Quarry Bank, the wheels of industry turned because children turned them. Today, the wheels of industry turn because children are trained to become workers before they are taught to be humans.

Only the machinery has changed.

Back then, it was looms and mills. Today, it is metrics and algorithms. But the question remains the same: are we extracting potential from the young, or investing in it?

The lambs in the neighbouring field didn’t know any of this, of course. They leapt. They bleated. They reminded my children – and me – of a world untouched by acceleration.

We cannot slow time. But we can choose where we place our attention.

And attention, now more than ever, is the most precious gift we can give. Not to machines, but to the minds that will inherit them.

Statistics of the Month

📈 AI accelerates – but skills lag

In just 18 months, AI jumped from the sixth to the first most in-demand tech skill in the world – the steepest rise in over 15 years. Various other reports show people lack these skills, representing a huge gap. 🔗

📉 Workplace engagement crashes

Global employee engagement has dropped to just 21% – matching levels seen during the pandemic lockdowns. Gallup blames poor management, with young and female managers seeing the sharpest declines. The result? A staggering $9.6 trillion in lost productivity. 🔗

🧒 Social media starts at age three

More than 50% of UK children aged 3–12 now have at least one social media account – despite age limits set at 13+. By age 16, 80% are active across TikTok, Snapchat, Instagram, and WhatsApp. Childhood, it seems, is now permanently online. 🔗

🤖 AI anxiety sets in early

According to Nominet’s annual study of 8-25 year olds in the UK, 53% have used an AI chatbot, and 54% worry about AI’s impact on future jobs. The next generation is both enchanted by and uneasy about their digital destiny. 🔗

🚨 Cybercrime rebounds hard

After a five-year decline, major cyber attacks are rising in the UK – up to 24% from 16% two years ago. Insider threats and foreign powers are now the fastest-growing risks, overtaking organised crime. 🔗

Thank you for reading Go Flux Yourself. Subscribe for free to receive this monthly newsletter straight to your inbox.

All feedback is welcome, via oliver@pickup.media. If you enjoyed reading, please consider sharing it via social media or email. Thank you.

And if you are interested in my writing, speaking and strategising services, you can find me on LinkedIn or email me using oliver@pickup.media.

One thought on “Go Flux Yourself: Navigating the Future of Work (No. 17)”